Nicole Herzog of Boise State University was awarded a Leakey Foundation Research Grant during our spring 2016 cycle for her project entitled “Chimpanzees in fire-altered landscapes: Investigating foundations for hominin fire exploitation.”

Dr. Jill Pruetz has been studying the behavior of the wild chimpanzees of Fongoli, Senegal, for 17 years. She has observed chimpanzees hunting with spears; she has looked on as chimpanzee youngsters learn to fish for termites and forage with family. She has also carefully noted other exceptional aspects of the behavior of these savanna-dwelling primates. In 2010, she with colleague Thomas LaDuke reported on the responses of this population to the dry season fire-regime that impacts a large portion of the animals’ home range each year. In that paper, they noted the savvy responses of chimpanzees to fire. The animals seemed able to read the fires, anticipating the direction and speed, and expertly maneuvering around them. They pondered the relevance of this phenomenon in the context of early human evolution and the role fire may have played in shaping our own species.

Following the 2010 publication, Pruetz continued to collect data on the behavior of her subjects in and around burned landscapes. Other important patterns emerged. Chimpanzees appeared to spend more time feeding in burned areas. They also used burn areas for travel. Did the chimpanzee’s knowledge of fire extend beyond the scope of safely navigating away from active fires? Were there other reasons to be fire-savvy?

In 2016, we were awarded a Leakey Foundation grant to explore these questions further. Our aim was to investigate fire at Fongoli, using the behavior of the chimpanzees as a model for aspects of early hominin response to burned landscapes. We sought to collect data on two issues thought to be critical in the reconstruction of human evolutionary history: 1) establishing foraging niches in savanna settings and, 2) the ranging behavior of a savanna-dwelling ape. We established two hypotheses to test during the 2016-2017 field season at Fongoli. The first was that burning will increase encounter rates for certain resources. Second, burned corridors will provide more direct routes to feeding trees; these routes will be used preferentially.

Fall 2016 involved rounding up all of the necessary gear to accurately measure encounter rates, paths of travel, and overall burning patterns. GPS trackers, data books, and field gear in hand, we began the project at the onset of the fire season in late November 2016. As the green grasses of the wet season begin to dry, horticulturalists living in the area use fire to clear the land, the trails, and the woodlands. As the heat of the dry season gathers, natural fires are common as well. With the help of dedicated Senegalese field assistants, we began intensively monitoring the occurrence of fires and the behavior of the chimpanzees in and around them. During that first month of study, we recorded nearly 40 small fires. We mapped each fire, recording the date of burning and total area impacted. It was a very exciting time! The smoke from fires could be seen for kilometers, and if you were close enough you could hear the intense sound of the bush ablaze.

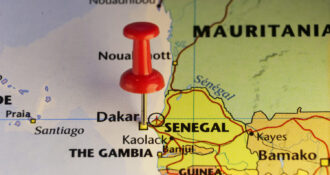

Nicole Herzog in a recent burn, showing height of grasses pre-fire ~6-7 feet tall at Fongoli, Senegal.

One afternoon as we surveyed a burn scar from the previous day’s fires we rounded a bend and caught sight of a flurry of bulky body and long tail leaping out of a bare tree that sat just on the edge of the burn. The blur moved about 10 meters into the wooded area behind, then turned to look back at us. It was a leopard. When we approached the leopard’s tree, we found it to be a perfect lookout over the newly burned plateau. Conveniently, it also looked over a well-worn trail that humans and apes alike use to travel through the area. We decided to stay close, wondering if the leopard or its prey might return. As we waited we heard the familiar calls of vervet monkeys from the nearby ravine. The vervets skirted the edge of the burn that day but never entered the scorched terrain. Several days later we did find them in the burn, just down the trail from where we’d seen the leopard. They appeared to be foraging well outside the ravine on the other side of the plateau. We watched as they ran wildly back across the newly bare expanse back to the safety of the unburned woods. This anecdote begs many other questions about the draw of burned areas for primates and the safety of their use. While burning may be a boon for savanna-dwelling primates, does it make them easy prey for smart predators – conversely could burning be a bust for ambush predators that rely on thick brush and dense vegetation to make their kills?

The Fongoli dry season lasts from November to April. As the dry-season months went on, we observed more burning. By the beginning of May we had recorded over 100 individual fires across the 85 km2 area that makes up the home range of the savanna-chimpanzees. These fires impacted no less than 75% of the total range. In conjunction with fire maps, we also recorded over 100 individual chimpanzee daily routes. These routes track the paths of travel that individual subjects embark on and typically span an entire day’s movements.

In May the rains came to Fongoli, and it is now nearly time for the dry season to begin again. The amount of data we were able to collect during this year of field-work is extraordinary, if not a little daunting. Now that field work is wrapped up for this project – though ongoing behavioral data collection is carried out all year at Fongoili – we’ve begun the process of sorting and organizing our maps and tracks, notes on feeding and fire related behavior. We will spend the next year analyzing all of this data for patterns that can help shed light on the ways fire impacts these animals. We hope to learn more about how they have learned to adapt, and even take advantage of, the force of fire. We have no doubt this information will provide answers to our hypotheses and will shed light on the role of fire in human evolution.

Comments 0