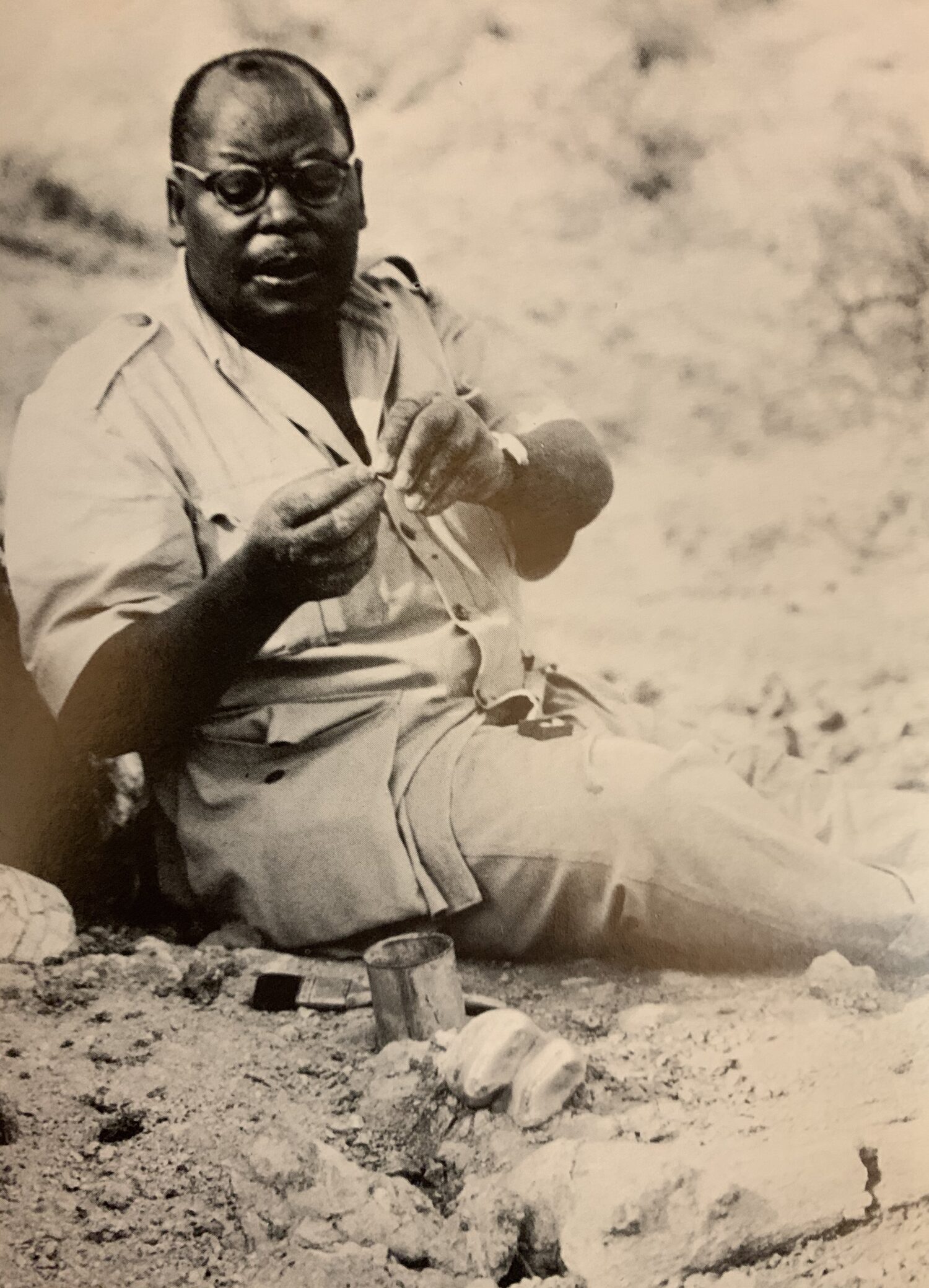

Fossil Finders is a series devoted to telling the stories of the people behind important fossil discoveries. In this installment, Leakey Foundation Fellow Carol Broderick brings us the story of Heselon Mukiri who made several important discoveries and worked with Louis Leakey since the beginning of Leakey’s career.

By Carol Broderick

In previous articles, it would seem that Kamoya Kimeu’s Hominid Gang learned most if not all of their paleoanthropology knowledge and techniques from the Leakeys, but the Leakeys did not pass on this information alone. In the late 1920s, Louis Leakey hired an assistant by the name of Heselon Mukiri. Mukiri was already Leakey’s friend. When Leakey was a boy living in Africa with his missionary parents and both boys were 13, they shared in initiation rites that would make them members of the same Kikuyu Mukanda age group. “My Kikuyu training taught me this,” Leakey wrote later in a National Geographic article, “if you have reason to believe that something should be in a given spot but you don’t find it, you must not conclude that it isn’t there. Rather, you must conclude that your powers of observation are faulty.” On Leakey’s return from Cambridge, he hired several of his Kikuyu acquaintances to work with him in Kenya. Heselon Mukiri was one of them.

Heselon Mukiri was also included in Louis’ Fourth East African Archaeological Expedition in 1934-35 in Kanam, Kenya. It was there, in the early 1930s, that Leakey had discovered the lower jaw of a hominid he called Homo kanamensis. This was the first new Homo designation Louis bestowed on one of his fossil finds, and its status was not lost on anthropologists across the globe. It was on this excursion that Peter Kent, a geologist on the expedition, referred to Mukiri as a “treasure” as he was already trained to not only look for fossils but to excavate them. While Mukiri attempted to find the original site of his earlier find, unsuccessfully to his great dismay, Mukiri and the other workers were already busy looking for new fossils.

It was at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania that Mary Nicol and Heselon Mukiri first met, and he was wary of this new woman in the field. The staff had all worked with and respected Frida Leakey, Louis’ first wife, and both their religious views and those of most of the world frowned on casual relationships. But Mary’s serious commitment to and passion for paleontology and the skills she brought to the field won even Mukiri’s respect. After a short while in the field, she wrote, “he now accepted me as a worthwhile member of the team and as someone who might even be worthy of Louis.”

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Mukiri continued to work with the Leakeys in the field. In 1948, on the second British-Kenya Miocene Research Expedition, he was there when Mary made an exciting discovery: a skull containing the face of a Proconsul – the first Proconsul skull containing such complete features excavated in East Africa. She and Heselon worked as a team reconstructing this exciting new face. He carefully searched each grain of sand, and as he found pieces of the skull, some incredibly tiny, he gave them to Mary Leakey. She worked on completing the complicated reconstruction, one of her special talents. Years later she wrote, “This was a wildly exciting find which would delight human paleontologists all over the world, for the size and the shape of a hominid [sic] skull of this age, so vital to evolutionary studies, could hitherto only be guessed at. Ours were the first eyes ever to see a Proconsul face.” As Mary Leakey left to present her find to the world, Mukiri was left to manage the staff and to continue excavating the site.

By the mid-1940s, Mukiri was clearly the leader of the group of workers vital to the success of the search for hominids. In 1949, Louis Leakey decided it was time to list Mukiri’s name as a formal member on the Kenya Miocene expedition permit. Although everyone who knew and worked with the Leakeys understood that this was an informal arrangement that had been going on for years, Africans were prohibited from excavating a site without the permit holder there. Sonia Mary Cole, a British anthropologist, author of Leakey’s Luck and one of Mary Leakey’s closest friends, recognized the rarity of Mukiri’s management position, calling him the “first ‘native’ permit holder.” She described him in this way: “Undisputed boss, as always dignified and rather unapproachable but with a well-developed sense of humor, he was respected by the others. Few could rival his eye for a fossil or his skill with plaster of Paris.”

In 1947, at an island in Lake Victoria called Rusinga Island, Mukiri was with Mary, Louis, and Jonathan Leakey, and a small group of Kikuyu workers when Louis discovered another Proconsul jaw of a Miocene ape, which along with further similar discoveries, in 1993 was given a new species name: Proconsul heseloni. It was recognized as the fourth species of this famous hominoid. How much the Leakeys and the paleontological world valued Heselon Mukiri’s work can be found in this unique designation.

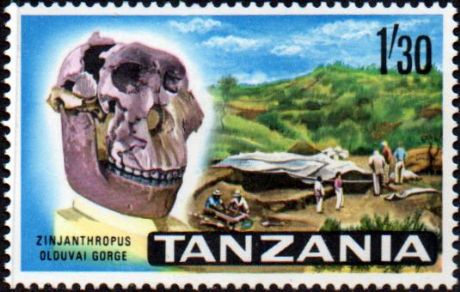

Mukiri was not only an excavation expert and the leader of the scientific team; he also excelled in the role of a fossil finder. In 1959 at Olduvai he discovered a hominid tooth in Bed l. It was on this same expedition that Mary discovered the skull of what would become known as Zinjanthropus boisei, (later assigned to another group, Australopithecus boisei) or Zinj, one of the most exciting paleoanthropological finds in history. In 1965, a Tanzanian postage stamp of Zinj was released. Mukiri’s image appears on that stamp, along with Mary and Louis Leakey and Dr. and Mrs. Melville Grosvenor of the National Geographic Society.

In the early ’60s, Louis Leakey became interested in a Miocene site at Lake Victoria called Fort Ternan. Because of the recent finds at Olduvai, Leakey realized that the world was waiting for more discoveries at this site, and he asked Mukiri to manage operations at the Fort Ternan site. Over the years, Mukiri discovered numerous unique and interesting animals there, many totally new to the scientific community. At the time, the Leakeys were busy finalizing the new Centre for Prehistory and Paleontology on the Coryndon museum grounds in Kenya and working on their Olduvai finds. Louis Leakey checked in, periodically, and it was on one of those visits that Heselon handed him a diminutive metal box that held two pieces of a primate’s upper jaw and a lower molar. It was later dated at 14 million years, a period of time with few hominoid fossils on record. Of special interest to Leakey was the slight depression below the eye socket in the cheekbone, a hominid trait. He was sure this hominoid may have been a branch, although a distant one, on our family tree. He named this ape Kenyapithecus wickeri after Fred Wicker, on whose land it was discovered. At this site, Mukiri’s crew also discovered new species of giraffe, mastodon, and rhinoceros. In 1962 the site was reopened, and several teeth, a section of the lower jaw, and a limb bone of Kenyapithecus were also discovered. Later, while working with the Leakeys at Olduvai Gorge, many pig fossils were found, two later named after Mukiri: Mesochoerus heseloni and Promesochoerus mukiri.

Heselon Mukiri retired in 1968. At his retirement, he was awarded a diploma and $1,000 by the National Geographic Society. Shortly after he retired Mary wrote: “The African staff, under the direction of Heselon Mukiri, deserve our sincere thanks for their consistently high standard of work. A number have shown outstanding ability, not only in excavation but also in recognizing fragmentary hominid material and in developing delicate fossils.”

Heselon Mukiri died in 1984. Over the many decades of the Leakeys’ expeditions, as Kikuyu and Kamba staff came and went, Mukiri stayed, fostering the transfer of knowledge to and from the fossil finders to the scientists as he played a vital role in the search for our ancestors.

Editor’s note: We are seeking additional photos of Heselon Mukiri. If you have one or know where we can find one, please contact [email protected].

Comments 0