Fossil Finders is a series devoted to telling the stories of the people behind important fossil discoveries. In this first installment, Leakey Foundation Fellow Carol Broderick brings us the story of the legendary Kamoya Kimeu.

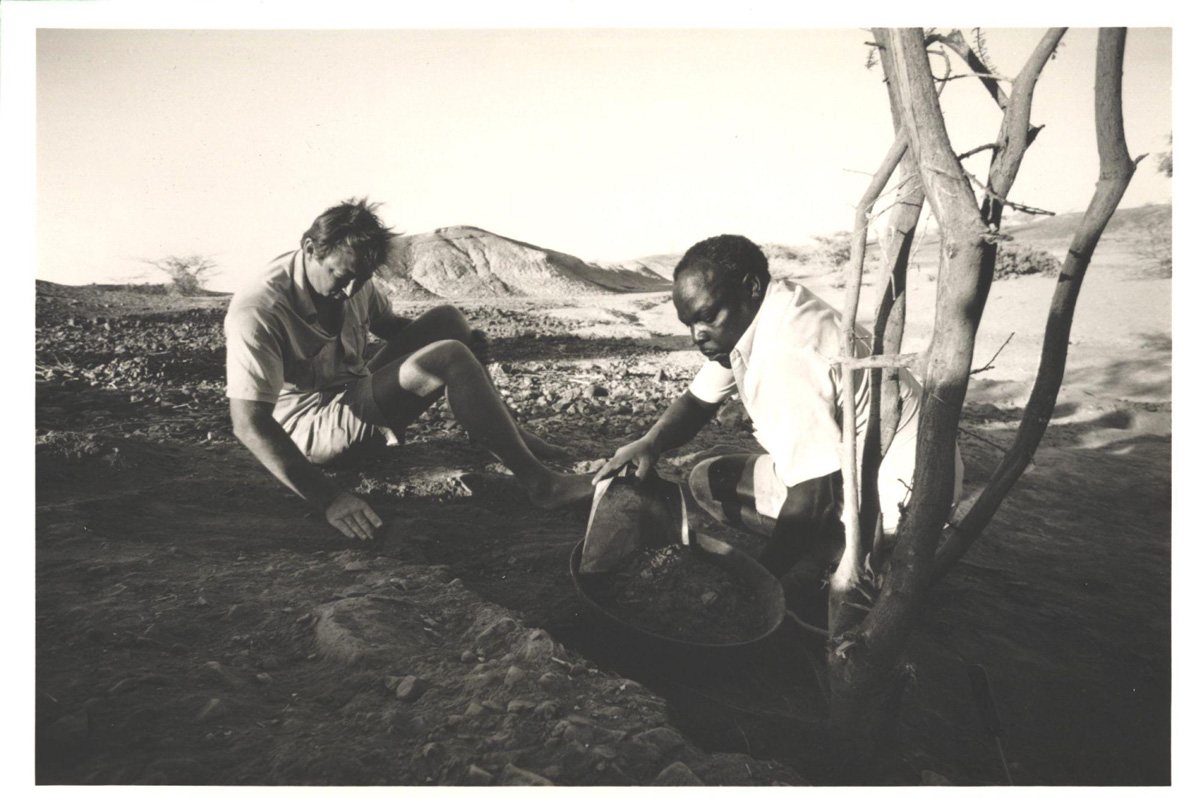

Kamoya Kimeu (right), partner of Richard Leakey (left) for two decades, turns up facial bones of a fossil Homo erectus under a thorn tree on the western shore of Kenya’s Lake Turkana. Photo by David L. Brill 1985, National Geographic Society, From The Leakey Foundation Archive

By Carol Broderick

Most paleontologists track their careers in terms of funding and expedition cycles, searching for fossils in finite windows of time and often spending months, even years waiting to return to promising sites. It is rare that someone is able to devote his or her life to searching for fossils, yet one man has done exactly that. That man is Kamoya Kimeu.

Kamoya Kimeu was 21 years old when he was approached by Louis Leakey to join his expedition as a field worker at Olduvai in 1960. Originally, he thought Leakey’s job description, which included “digging for bones,” entailed grave digging. “We didn’t know then about hominid bones, that there were such things. I thought we were coming to dig some graves of dead people,” Kimeu recalled. In his Kamba tribe, touching the dead, as in many tribes, was considered a serious violation. Yet Leakey, who enthusiastically explained the work to be done in fluent Kikuyu, won Kimeu’s trust. “I could see that this mzunga was not like the others; he was talking to us like a person.” And this was the beginning of Kamoya Kimeu’s legendary fossil hunting career.

When Mary Leakey became “Director of Excavations” at Olduvai, she decided to hire all Kamba workers instead of the Kikuyu workers Louis had used. Kimeu, who is Kamba, continued to work for Louis and Mary Leakey and then Richard and Meave Leakey for the next two decades. His knowledge of Kikuyu, Swahili, and English was instrumental in working with both staff and the other researchers. In 1977, Kameu became curator of prehistoric sites for the National Museums of Kenya; he also continued to work with the Leakeys in the field.

View of Olduvai Gorge, one of the most important paleoanthropological sites in the world. Great Rift Valley, Tanzania, Eastern Africa.

How did this man, the son of a goat herder, go on to become what some paleontologists believe is the greatest fossil finder of all time?

When Mary Leakey chose the Kamba tribe as her staff, she did so because she had seen the intricate chains and wood carvings they made. She felt that members of the tribe had the potential to master skills to do difficult work that required diligence and patience, carefulness and attentiveness. Kamoya Kimeu embodied these traits as he set his sights on the mandibles and skulls of our ancestors. As a boy living in the bush, Kimeu had to learn survival skills, to find water and food for the animals, and to read the land. This knowledge of the East African landscape proved to be invaluable in the field.

Kimeu also learned his skills from the best paleontologists in the field at that time. Louis Leakey taught him about evolution and paleontology. Mary Leakey taught him excavation techniques which are still valued by researchers in the field. Richard Leakey, too, passed on his attention to detail. Before Richard became a renowned paleontologist, Kimeu worked with him in an animal skeleton business. Each bone was carefully labeled, and Kimeu soon was able to distinguish one animal from another. All of this education enabled him to be a master of his trade.

Richard Leakey remarked on Kimeu’s incredible talent at finding fossils from everything from elephants to australopithecines: “To some of our visitors who are inexperienced in fossil-hunting, there is something almost magical in the way Kamoya or one of his team can walk up a slope that is apparently littered with nothing more than pebbles and pick up a small fragment of black, fossilized bone, announcing that it is, say, part of the upper forelimb of an antelope. It is not magic, but an invaluable accumulation of skill and knowledge.”

Kimeu also has his own theory concerning his incredible discoveries. In an article published in National Geographic, he said that he actually speaks to our ancestors in an imaginary language, Kikoshwa, and they tell him where to find the fossils! But perhaps the most logical answer lies in the fact that he spent so many days, so many years in the field. As the article’s author wrote, this “irrepressible energy” and the fact that Kimeu rarely took time off from his excavating, undoubtedly increased his chances of finding fossils.

Kimeu’s discoveries have not only been numerous; they have also been incredibly important to the study of paleoanthropology. It is impossible to list all of the fossils Kamoya himself has found. His fellow fossil finders, members of Kimeu’s “Hominid Gang,” also made their own discoveries, which will be part of a future “Fossil Finders” series article.

Here are a few of Kamoya Kimeu’s most important discoveries:

- In January of 1964 at the Peninj site near Lake Natron in Tanzania, Kimeu, working with Richard Leakey and Glynn Isaac, found an entire mandible of a Paranthropus boisei (later identified as an Australopithecus boisei ) known as the Peninj Mandible. This find was particularly important to Louis Leakey, who thought that this robust form of hominid was not ancestral to Homo; Louis believed this discovery confirmed that assumption. At approximately two million years old, this hominid would have been a contemporary of Homo habilis and not its direct ancestor as some scientists had proposed.

- In 1968, again on an expedition with Richard in the Omo valley of Ethiopia, Kimeu discovered an early Homo sapiens skull. This discovery was instrumental because until then, no one believed Homo sapiens could be this old. Dated at 130,000 years old, until this discovery, many anthropologists believed that Homo sapiens had not appeared until after the Neanderthals, or approximately 60,000 years ago at the latest. This discovery also proved that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were contemporaries, an important piece of the complex human story.

- Kimeu worked with Richard, again, in the late 60’s at Allia Bay in Lake Turkana. They endured extremely difficult conditions: dangerous heat (105-110 degrees) and blistering wind, excavating over twenty miles per day because of the huge number of fossils. It was at Allia Bay that Kimeu found two teeth of Australopithecus africanus. On the same trip, at Ileret River in Northern Kenya, Kimeu found part of another Australopithecus jawbone, important because the Omo deposits were approximately 150,000 years old or perhaps even younger while the Lake Turkana deposits were dated at 1-4 million years old.

- By 1973, research at Koobi Fora was ongoing; however, Richard Leakey, who was busy running several museums in Nairobi, rarely searched for fossils himself. Kimeu’s team managed to find more than twenty hominid fossils that season. It was here that Kamoya Kimeu located a new fossil, KNM-ER 1813, a Homo specimen with a relatively small braincase. This gracile hominid resembled the Australopithecus africanus discoveries of South Africa. Its significance was that it indicated that at least one Homo group and both kinds of Australopithecines’s lived between one and three million years ago. It was dated between 1.8-1.9 MYO, but this date was not without controversy. Richard believed that it was the fossil of Homo habilis, but this, too, was also hotly debated.

- Probably Kimeu’s most famous fossil discovery was that of an almost complete Homo erectus skeleton labeled KNM-WT 15000 but known in paleoanthropological circles as Turkana or Nariokotome boy. Found in 1984 at Kenya’s Lake Turkana where Richard Leakey and Alan Walker were doing research, it was described as a young male between 9 and 11 years old and dated at approximately 1.6- 1.5 million years old. The sequence of events of this discovery was by that time a familiar one. While walking next to a slope of black rocks next to the dry Nariokotome River, Kimeu noticed a dark bit of bone. “How he found it, “Walker wrote, “I’ll never know.” Kimeu radio phoned Richard about his discovery, their usual mode of communication, suggesting that it might be part of a Homo erectus skull. Richard arrived quickly, confirming Kimeu’s classification and marveling at what would become the first skeleton of a Homo erectus and the most complete skeleton since Lucy! Some paleontologists classified the remains as Homo ergaster, but today it is considered to be an example of Homo erectus.

- In 1985 Kimeu found a partial skull of a new hominoid about 60 miles from Nariokotome. It possessed a particularly long muzzle and appeared very different from all previous hominoid/ape discoveries. Richard and Meave named it Turkanopithecus kalakolensis.

- In 1994, working with Meave Leakey at Kanapoi in Southwest Turkana, Kimeu found two parts of a hominid shinbone; others found more of this fossil and it was dated at approximately four million years. It was given a new species name, Australopithecus anamensis.

This list does not include all of Kamoya Kimeu’s finds, but it shows how his discoveries were important not only to the controversial classifications proposed by the Leakeys but to the science of paleontology itself. As these finds were documented in scientific journals, it became clear that the Ph.D. next to a scientist’s name was essential in the actual excavation, naming and formal description of the fossils. East African staff were not always given recognition by those who depended on their discoveries for their scientific careers. Kamoya Kimeu was one of the first native East African fossil finders to be given this recognition.

Certainly, the Leakeys recognized his unique talents. At Richard Leakey’s camp, Kimeu sat with Richard and the other scientists at the “management table,” and by 1972, he had “assumed control of field operations” for Richard in his absence as he was busy running several museums in Kenya.

In 1985 Kimeu was awarded the National Geographic Society La Gorce Medal by Ronald Reagan at the White House. This prestigious award is for “accomplishment in geographic exploration, or in the sciences, or for public service to enhance international understanding.”

The media, too, singled out Kimeu for his contributions. National Geographic Society President Gilbert Grosvenor wrote, “Thanks to his work, our forerunners of the distant past have begun to speak not only Kikoshwa but the language of all mankind.”

There is probably no greater recognition than to have fossils named after you. Two fossil primates have been given this honor: Kamoyapithecus hamiltoni and Cercopithecoides kimeui.

Today, it is still relatively rare to find paleontologists who live in the field. Of course, Louis and Mary Leakey were examples of two people who introduced Kimeu to this life, and now Meave and Louise Leakey carry on that tradition.

In 1994 Kimeu called Meave, now head of paleontology at the National Museums of Kenya. He was at Kanapoi in Southwest Turkana. He and his Hominid Gang colleagues brought her to a site where Kimeu had found yet another piece of a shinbone, another one of his gang an upper jaw of a hominid. Once again, the Leakeys and Kimeu were involved in unearthing another of his important discoveries. Kimeu cradled the teeth in his hands and said, ‘Surely this is where we come from,” the words of a wise man who has brought life to fossils that have changed our world and the shed light on the history of our closest ancestors.

Comments 2

This is a wonderful article! It’s good to know that the Leakeys worked with the very people on whose continent these discoveries were made. They were also fortunate to have found the very talented Kimeu. His discoveries are amazing!

Irja: It was great fun writing this article – almost like re-discovering the fossils! I’ll follow this up with several others about other fossil finders who people may not know about. Without these men, our knowledge of our ancestors would be sorely lacking….