The oldest distinguishing feature between humans and our ape cousins is our ability to walk on two legs – a trait known as bipedalism. Among mammals, only humans and our ancestors perform this atypical balancing act. New research led by a Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine professor of anatomy with support from The Leakey Foundation provides evidence for greater reliance on terrestrial bipedalism by a human ancestor than previously suggested in the ancient fossil record.

Scott W. Simpson led an analysis of a 4.5 million-year-old fragmentary female skeleton of the human ancestor Ardipithecus ramidus that was discovered in the Gona Project study area in the Afar Regional State of Ethiopia.

This is a fossil hominin talus from site GWM67 (2005) at the time of its discovery. Photo credit: Case Western Reserve University

The newly analyzed fossils document a greater, but far from perfect, adaptation to bipedalism in the Ar. ramidus ankle and big toe than previously recognized. “Our research shows that while Ardipithecus was a lousy biped, she was somewhat better than we thought before,” said Simpson.

Fossils of this age are rare and represent a poorly known period of human evolution. By documenting more fully the function of the hip, ankle, and foot in Ardipithecus locomotion, Simpson’s analysis helps illuminate current understanding of the timing, context, and anatomical details of ancient upright walking.

Previous studies of other Ardipithecus fossils showed that it was capable of terrestrial bipedalism as well as being able to clamber in trees, but lacked the anatomical specializations seen in the Gona fossil examined by Simpson. The new analysis, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, thus points to a diversity of adaptations during the transition to how modern humans walk today. “The fact that Ardipithecus could both walk upright, albeit imperfectly, and scurry in trees marks it out as a pivotal transitional figure in our human lineage,” said Simpson.

Key to the adaptation of bipedality are changes in the lower limbs. For example, unlike monkeys and apes, the human big toe is parallel with the other toes, allowing the foot to function as a propulsive lever when walking. While Ardipithecus had an offset grasping big toe useful for climbing in trees, Simpson’s analysis shows that it also used its big toe to help propel it forward, demonstrating a mixed, transitional adaptation to terrestrial bipedalism.

Discoverers of the GWM67 locality and major hominin fossils (2005).

Asa Hamad Humet (left), Ali Ma’anda Datto (right). Image credit: Scott Simpson, CWRU School of Medicine.

Specifically, Simpson looked at the area of the joints between the arch of the foot and the big toe, enabling him to reconstruct the range of motion of the foot. While joint cartilage no longer remains for the Ardipithecus fossil, the surface of the bone has a characteristic texture which shows that it had once been covered by cartilage. “This evidence for cartilage shows that the big toe was used in a more human-like manner to push off,” said Simpson. “It is a foot in transition, one that shows primitive, tree-climbing physical characteristics but one that also features a more human-like use of the foot for upright walking.” Additionally, when chimpanzees stand, their knees are “outside” the ankle, i.e., they are bow-legged. When humans stand, the knees are directly above the ankle – which Simpson found was also true for the Ardipithecus fossil.

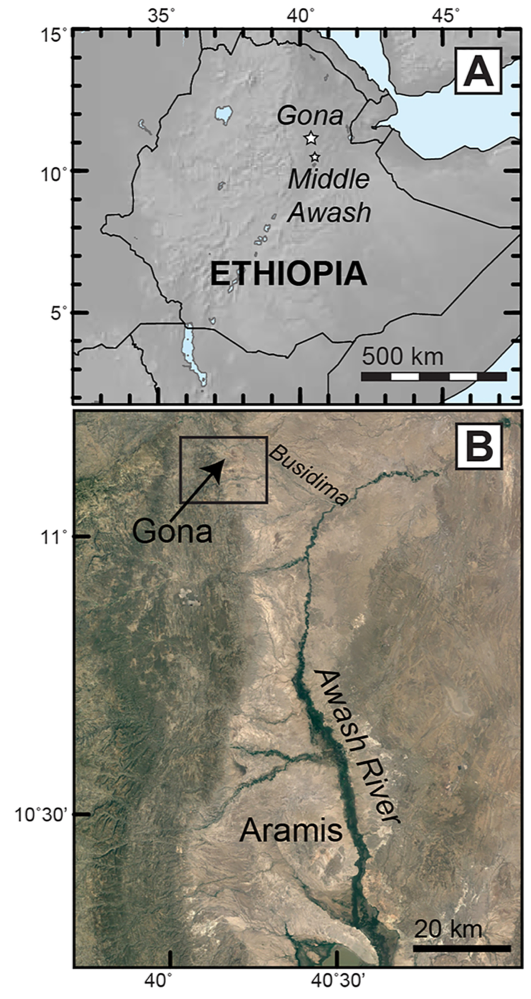

Location of the Gona Project study area. Derived from Simpson et al 2019. Image credit: Scott Simpson, CWRU School of Medicine.

The Gona Project has conducted continuous field research since 1999 with support from The Leakey Foundation. The study area is located in the Afar Depression portion of the eastern Africa rift and its fossil-rich deposits span the last 6.3 million years. Gona is best known as documenting the earliest evidence of the Oldowan stone tool technology.

The first Ardipithecus ramidus fossils at Gona were discovered in 1999 and described in the journal Nature in 2005. Gona has also documented one of the earliest known human fossil ancestors – dated to 6.3 million years ago. The Gona Project is co-directed by Sileshi Semaw, a research scientist with the CENIEH research center in Burgos, Spain, and Michael Rogers of Southern Connecticut State University. The geological and contextual research for the current research was led by Naomi Levin of the University of Michigan, and Jay Quade of the University of Arizona.

This research was made possible by use of the human and ape skeletal collections housed at the Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Major financial support was provided by The Leakey Foundation, Spain’s Ministerio de Economia, Industria y Competitividad, Marie Curie EU Integration Grant, U.S. National Science Foundation, Case Western Reserve University, the National Geographic Society, and the Wenner-Gren Foundation.

Simpson, S., et al. “Ardipithecus ramidus postcrania from the Gona Project area, Afar Regional State, Ethiopia.” Journal of Human Evolution. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.12.005

This news release was provided by Case Western Reserve University.

Comments 0