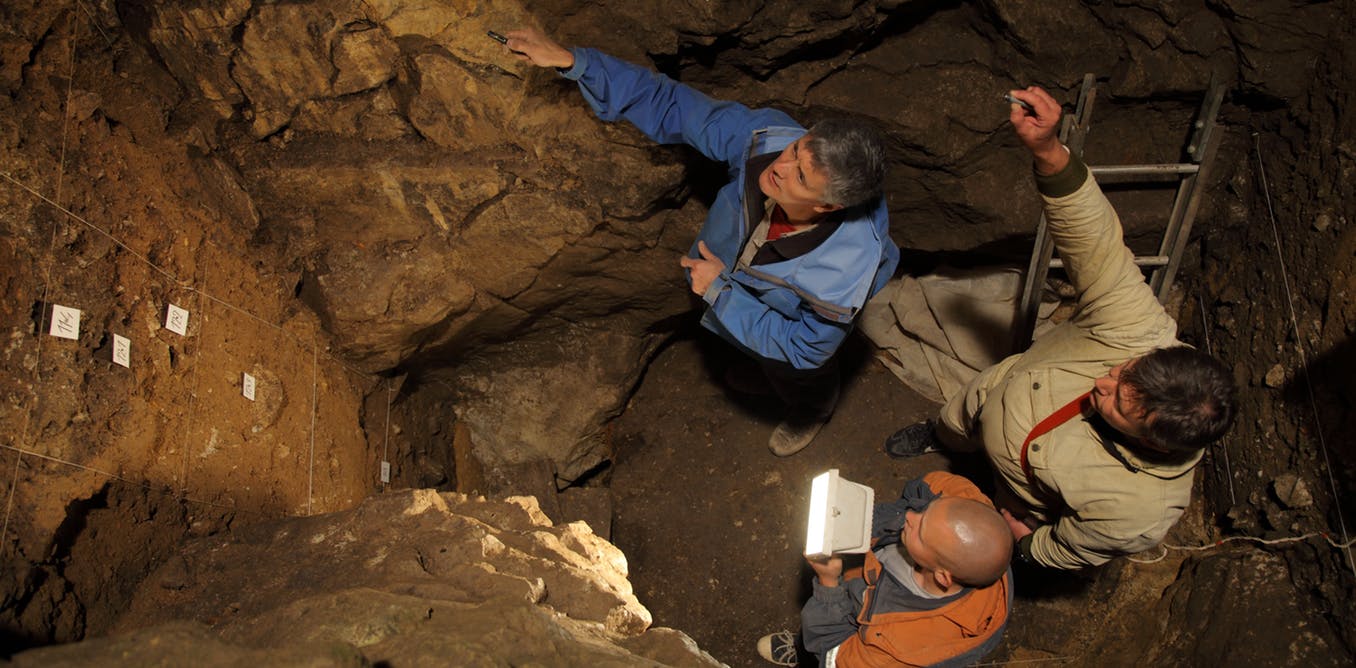

Richard ‘Bert’ Roberts, Vladimir Uliyanov and Maxim Kozlikin (clockwise from top) examining sediments in the East Chamber of Denisova Cave. Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, author provided.

Zenobia Jacobs, University of Wollongong; Bo Li, University of Wollongong; Kieran O’Gorman, University of Wollongong, and Richard ‘Bert’ Roberts, University of Wollongong

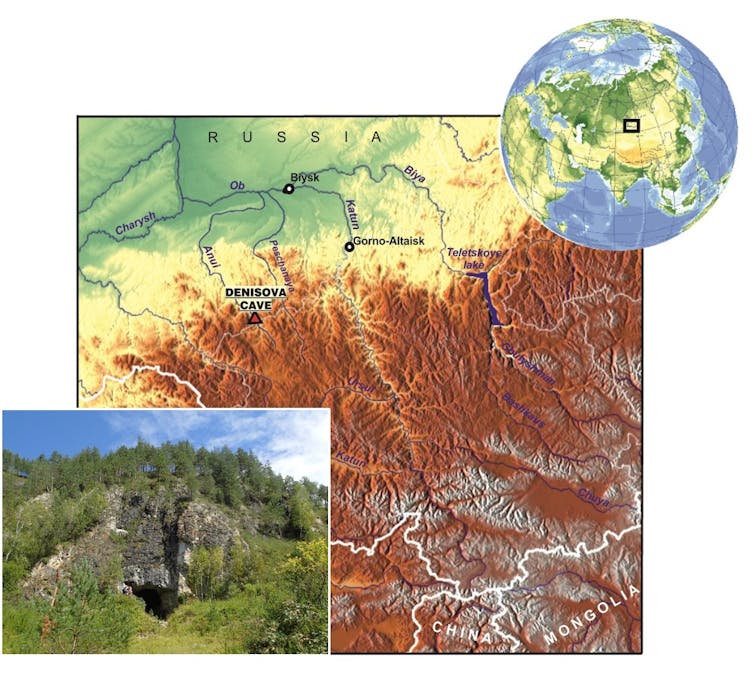

We know that some modern human genomes contain fragments of DNA from an ancient population of humans called Denisovans, the remains of which have been found at only one site, a cave in what is now Siberia.

Two papers published in Nature give us a firmer understanding of when these little-known archaic humans (hominins) lived.

Denisovans were unknown until 2010, when their genome was first announced. The DNA was obtained from a girl’s fingerbone found buried in Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia.

The new studies provide the first robust timeline for the Denisovan fossils and DNA recovered from the cave sediments, as well as the environments that the Denisovans experienced.

A few Neanderthal fossils have also been retrieved from the site, along with their genetic traces in the sediments at Denisova Cave, which was first excavated 40 years ago.

Modern humans (Homo sapiens) arrived later, making the site unique in the world as home to three groups of humans at various times.

All fossils of Denisovans and Neanderthals, and hominin bones not assigned to either group, discovered at Denisova Cave. Next to each fossil is the specimen number (for example, Denisova 2 in the top-left corner). Zenobia Jacobs, author provided.

Who were the Denisovans?

We currently know much more about the DNA of Denisovans than we do about their physical appearance, as hominin fossils are exceedingly rare at the site.

Besides the fingerbone, a total of three teeth have been genetically identified as Denisovan. The DNA from a tiny fragment of long bone from the daughter of Denisovan and Neanderthal parents provides direct evidence that the two groups met and interbred at least once.

We know frustratingly little about the geographic distribution and demography of the Denisovans, except for the head-scratching finding that Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans are the only people alive today with substantial amounts of Denisovan DNA in their genome.

But while hominin fossils are few and far between at Denisova Cave, the deposits contain thousands of artifacts made from stone. The upper layers also contain artifacts crafted from other materials, including ornaments made of marble, bone, animal teeth, mammoth ivory and ostrich eggshell. There are also animal and plant remains that bear witness to past environmental conditions.

Selection of artifacts from Denisova Cave. a, Upper Palaeolithic; b, Initial Upper Palaeolithic; c, middle Middle Palaeolithic; and d, early Middle Palaeolithic. Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, author provided.

Dating the Denisovans

Despite the importance of Denisova Cave to studies of human evolution, the history of the site and its inhabitants has persisted as a puzzle, due to the lack of a reliable timescale for the cave deposits and their contents.

With the publication of the two new papers, some of the critical pieces of this puzzle now fall into place.

The new studies build on the detailed work carried out by our Russian colleagues over several decades in all three chambers of Denisova Cave. They have painstakingly documented the complex layering of the deposits, along with the excavated cultural, animal and plant remains.

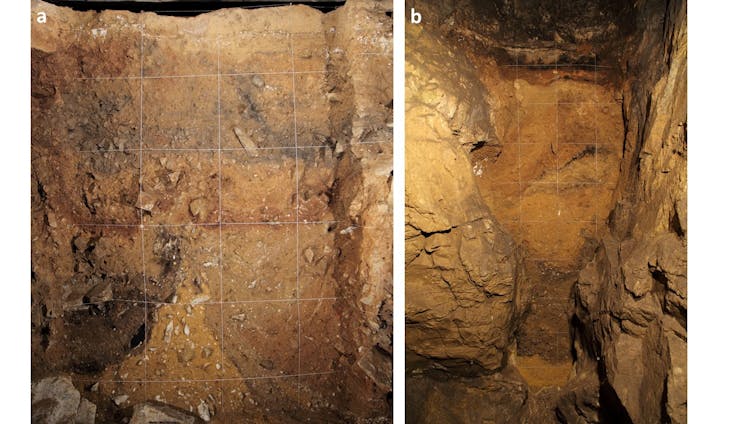

Sediment profiles (stratigraphy) in Denisova Cave: a, Main Chamber; b, East Chamber. The string lines in each photo are 50 cm apart. Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, author provided.

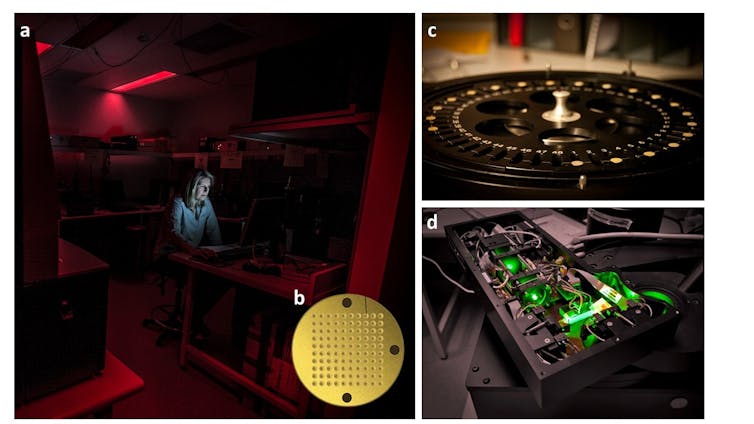

We used optical dating to determine when the sediments were last exposed to sunlight and deposited in the cave. Optical dating has been applied to archaeological sites around the world, with the minerals quartz and potassium feldspar most often used.

We measured more than 280,000 individual grains of these minerals from more than 100 samples using a combination of well-established and new procedures.

This enabled us to carry out a variety of experimental cross-checks, identify parts of the deposit that had been disturbed, date the oldest sediment layers, and construct a robust chronology for the site.

Optical dating of sediments: a, Zenobia Jacobs in the red-lit laboratory at the University of Wollongong; b, Sample holder for 100 individual sand-sized grains; b, Sample holders loaded onto carousel for optical dating of individual grains; d, green laser beam used to stimulate quartz grains in optical dating. University of Wollongong/Erich Fisher, author provided.

To better constrain the ages of the hominin fossils, our colleagues at the University of Oxford, UK, and two of the Max Planck Institutes in Germany developed a new statistical (Bayesian) model.

The new studies show that hominins have occupied the site almost continuously through relatively warm and cold periods over the past 300,000 years, leaving behind stone tools and other artifacts in the cave deposits.

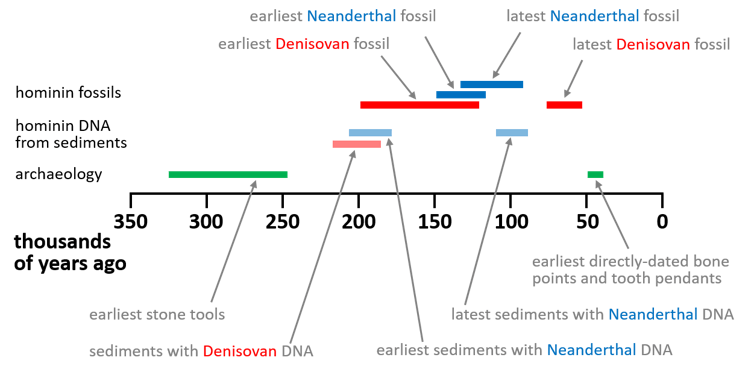

Fossils and DNA traces of Denisovans are found from at least 200,000 to 50,000 years ago, and those of Neanderthals from between 200,000 and 100,000 years ago. The girl with mixed ancestry reveals that the two groups of hominins met and interbred around 100,000 years ago.

Summary timeline for the archaeology, hominin fossils and hominin DNA retrieved from the sediments at Denisova Cave. All age ranges are shown at the 95.4% confidence interval. Bert Roberts, author provided.

Although Denisovans persisted at the site until 50,000 years ago, this does not preclude their later survival elsewhere. They were evidently a hardy bunch, living through multiple episodes of the cold Siberian climate before finally going extinct.

An incomplete history

We now know much more about the life and times of the Denisovans, but there are still many unanswered questions.

For example, we don’t know the nature of any encounters between them and modern humans, who were already present in other parts of Asia and in Australia by 50,000 years ago.

So while our understanding of the history of Denisovans has come a long way since 2010, there are still many missing pieces of this intriguing puzzle.

Zenobia Jacobs, Professor, University of Wollongong; Bo Li, Principal Research Fellow in Archaeological Science, University of Wollongong; Kieran O’Gorman, PhD candidate, University of Wollongong, and Richard ‘Bert’ Roberts, Director, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH), University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments 0