Thierra K. Nalley is an assistant professor at Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, California. She was awarded a Leakey Foundation Research Grant in our spring 2015 cycle for her project “Ontogeny of the Thoracolumbar Transition in Extant Hominoids and Australopithecus.”

The spinal column and vertebrae of Selam, a 3.3 million-year-old Australopithecus afarensis fossil discovered by Leakey Foundation grantee Zeresenay Alemseged in 2000. Photo: Zeresenay Alemseged

The spinal column is a critical region for understanding the evolution of bipedal walking because the joints between the vertebrae are involved in back movements and the formation of the lumbar lordosis, a curve in the lower back that allows humans to walk upright. Differences in vertebral anatomy between apes and humans have long provided an important framework for inferring postural and locomotor behaviors of fossil human relatives, but little is known about how and when these differences appear during growth. “To investigate vertebral development, we measured skeletal variation in the joints of lower vertebral column of juvenile and adult great apes, humans, and fossils attributed to Australopithecus and Homo erectus,” says Thierra Nalley, first author of the new study published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

The authors found that adult chimpanzees and humans experience more change in vertebral shape during development in comparison to gorillas and orangutans. This means that the joints of adult chimpanzees and human vertebrae differ from those of younger individuals, while gorillas and orangutans are more similar across age groups. Even though humans and chimpanzees have similar joint configurations as adults, humans are distinct because they reach adultlike shapes much earlier in development, usually by the time the first adult teeth begin erupting. Chimpanzees do not reach adult vertebral shape until later, only after all baby teeth are replaced.

Dr. Nalley with juvenile chimpanzee specimens on loan from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County at Western University of Health Sciences. Credit: Thierra Nalley.

Insight into the evolution of bipedality

“The fossil specimens indicate that early hominins also achieved adult vertebral shape early in development, like modern humans. This study highlights the importance of using developmental data to understand the transition to bipedality, including the possibility of gaining novel insights that are not apparent from adult comparisons,” says Zeresenay Alemseged, senior author of the study.

“These findings support a number of studies linking skeletal growth and developmental shifts in locomotor and postural behaviors in apes and humans,” says Nalley. “Our work suggests that the early acquisition of adultlike joint shapes in the vertebrae of fossil hominins may be an evolutionary innovation related to establishing stability and balance of the upper body as young individuals are learning to walk upright.”

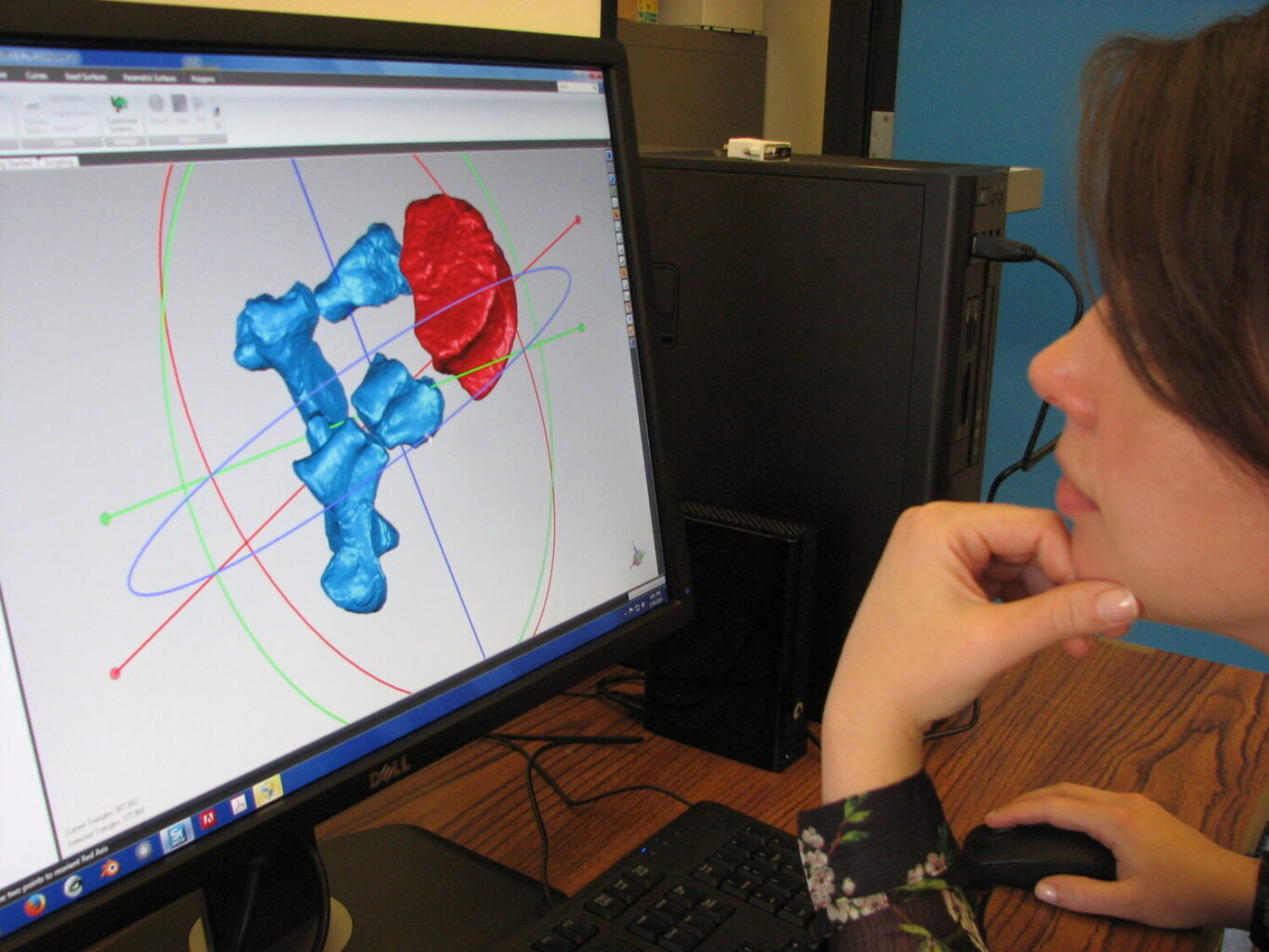

Thierra K. Nalley examines a digital reconstruction of the fossil hominin DIK 1-1, representing a juvenile specimen of Australopithecus afarensis.

The paper is published in the September issue of the Journal of Human Evolution with co-authors Jeremiah Scott at Western University of Health Sciences, Carol V. Ward at the University of Missouri-Columbia, and Zeresenay Alemseged at the University of Chicago.

Comments 0