Illustration by Andrey Atuchin

A new Leakey Foundation-supported study published Feb. 24 in the journal Royal Society Open Science documents the earliest-known fossil evidence of primates. This discovery illustrates the initial radiation of primates 66 million years ago, following the mass extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs and led to the rise of mammals.

Leakey Foundation grantee Stephen Chester, an assistant professor of anthropology and paleontologist at the Graduate Center, CUNY and Brooklyn College, was part of a team of 10 researchers from across the United States who analyzed several fossils of Purgatorius, the oldest genus in a group of the earliest-known primates called plesiadapiforms. These ancient mammals were small-bodied and ate specialized diets of insects and fruits that varied across species.

This discovery is central to primate ancestry and adds to our understanding of how life on land recovered after the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event that wiped out all dinosaurs, except for birds.

“This discovery is exciting because it represents the oldest dated occurrence of archaic primates in the fossil record,” Chester said. “It adds to our understanding of how the earliest primates separated themselves from their competitors following the demise of the dinosaurs.”

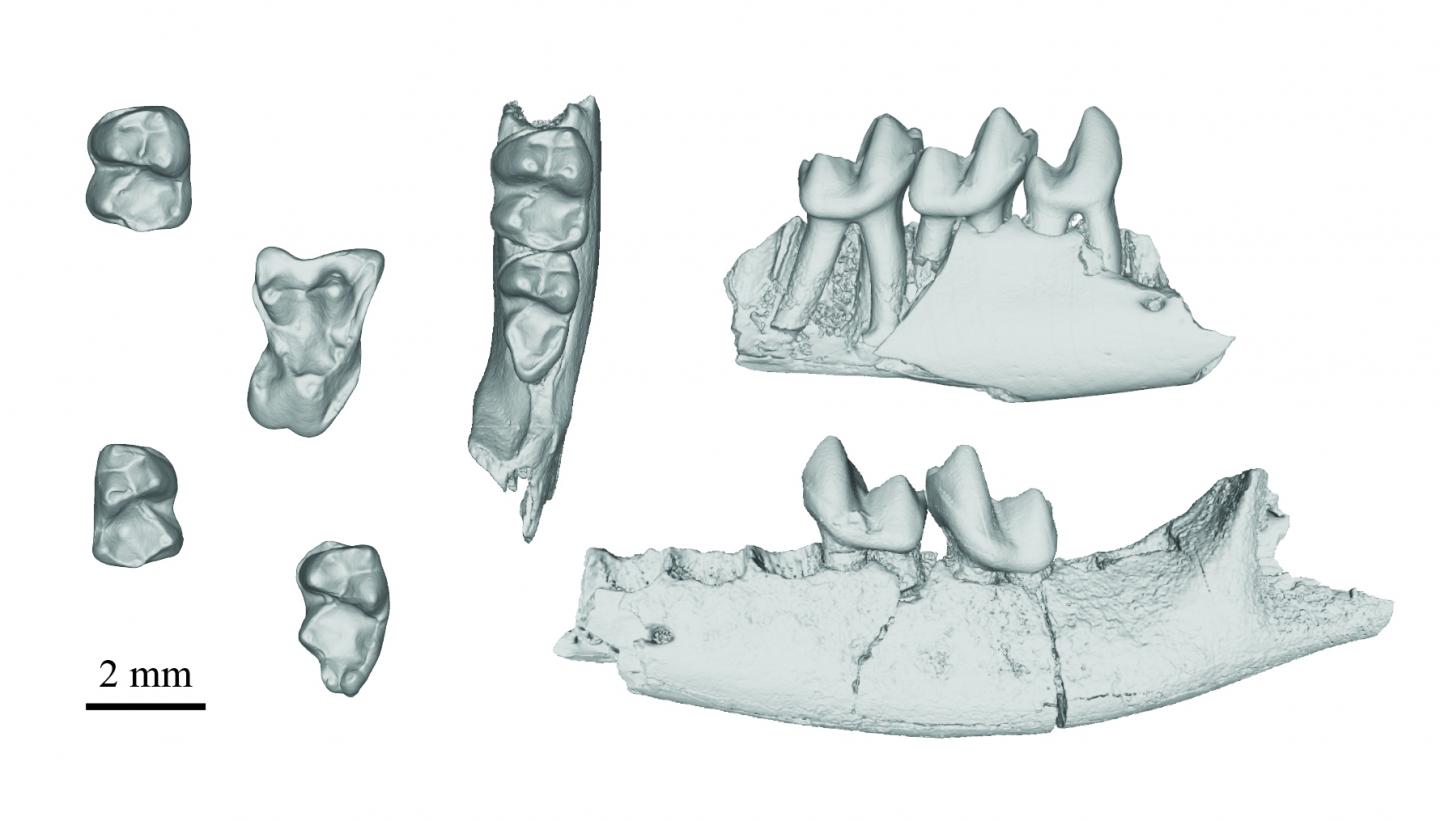

Chester and Gregory Wilson Mantilla, Burke Museum Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology and University of Washington biology professor, were co-leads on this study, where the team analyzed fossilized teeth found in the Hell Creek area of northeastern Montana. The fossils, now part of the collections at the University of California Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley, are estimated to be 65.9 million years old, about 105,000 to 139,000 years after the mass extinction event.

Based on the age of the fossils, the team estimates that the ancestor of all primates (the group including plesiadapiforms and today’s primates such as lemurs, monkeys, and apes) likely emerged by the Late Cretaceous–and lived alongside large dinosaurs.

“It’s mind blowing to think of our earliest archaic primate ancestors,” said Wilson Mantilla. “They were some of the first mammals to diversify in this new post-mass extinction world, taking advantage of the fruits and insects up in the forest canopy.”

Image courtesy of Gregory Wilson Mantilla/Stephen Chester

The fossils include two species of Purgatorius: Purgatorius janisae and a new species described by the team named Purgatorius mckeeveri. Three of the teeth found have distinct features compared to any previously known Purgatorius species and led to the description of the new species.

Purgatorius mckeeveri is named after Frank McKeever, who was among the first residents of the area where the fossils were discovered, and also the family of John and Cathy McKeever, who have since supported the field work where the oldest specimen of this new species was discovered.

“This was a really cool study to be a part of, particularly because it provides further evidence that the earliest primates originated before the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs,” said co-author Brody Hovatter, a UW graduate student in Earth and space sciences. “They became highly abundant within a million years after that extinction.”

“This discovery is exciting because it represents the oldest dated occurrence of archaic primates in the fossil record,” said Chester. “It adds to our understanding of how the earliest primates separated themselves from their competitors following the demise of the dinosaurs.”

Earliest Palaeocene purgatoriids and the initial radiation of stem primates R. Soc. open sci.8210050 http://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.210050

The team of researchers who collaborated alongside Chester and Wilson Mantilla in this latest discovery includes William Clemens, University of California Museum of Paleontology; Jason Moore, University of New Mexico; Courtney Sprain, University of Florida and University of California, Berkeley; Brody Hovatter, University of Washington; William Mitchell, Minnesota IT Services; Wade Mans, University of New Mexico; Roland Mundil, Berkeley Geochronology Center; and Paul Renne, University of California, Berkeley.

This story was written with materials provided by the University of Washington and The Graduate Center of The City University of New York/Brooklyn College.

Comments 0