In the News | Journal Article

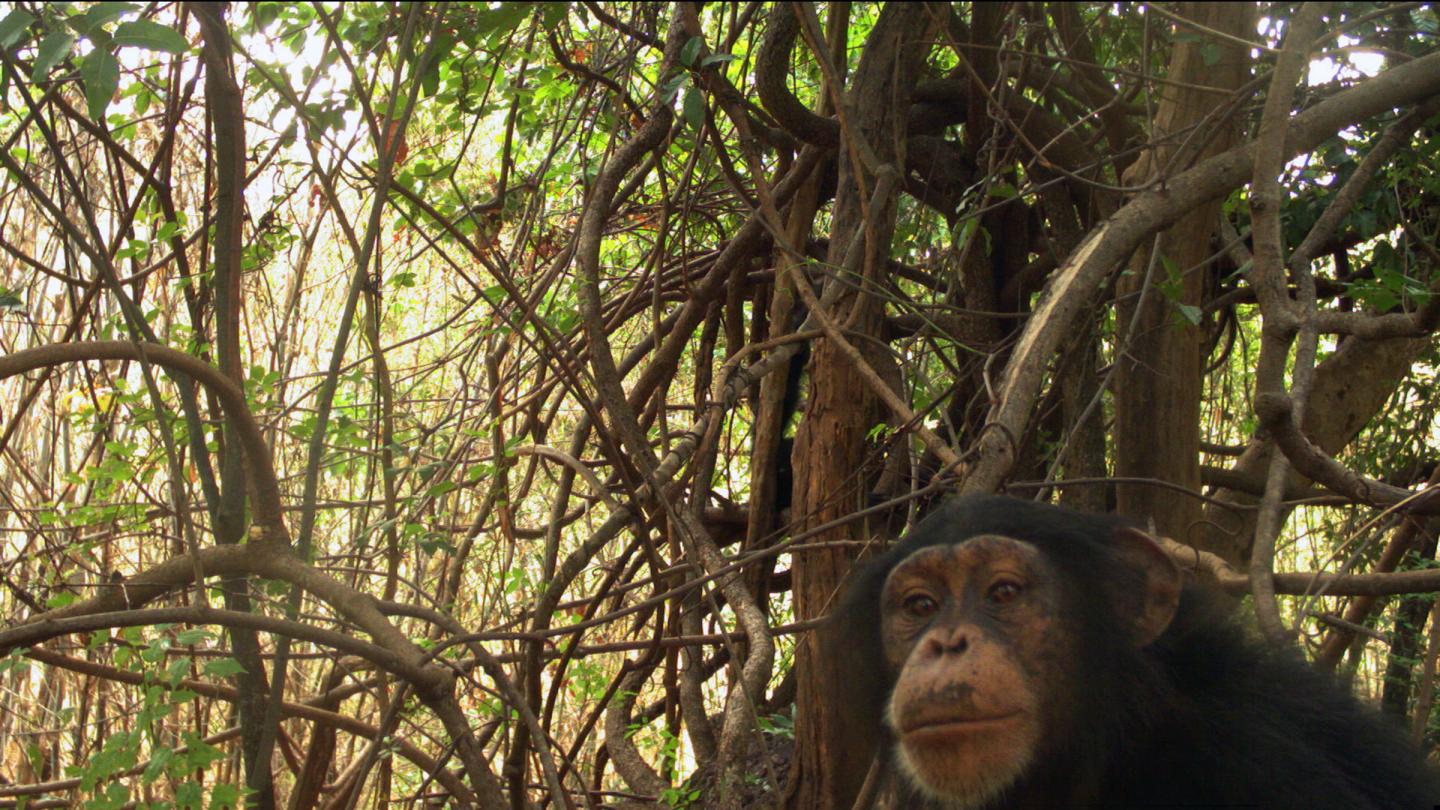

The West African chimpanzee population has declined by nearly 80 percent in recent decades. Habitat loss is threatening their livelihoods across the continent, and especially in Senegal, where corporate mining has started eating up land in recent years.

The geographical distribution of West African chimps in Senegal overlaps almost perfectly with gold and iron ore deposits, and unfortunately for the chimps, mining is a key piece of the country’s development strategy.

A new study of animal populations from inside and outside a protected area in Senegal called Niokolo-Koba National Park, shows that protecting such an area from human interaction and development preserves not only chimps but many other mammal species. The findings were published in the journal Folia Primatologica.

“We saw the same number of chimpanzee species inside and outside the park, but more species of carnivores and ungulates in the protected area,” said Leakey Foundation grantee Stacy Lindshield, a biological anthropologist at Perdue University.

Although habitat loss is the biggest threat to West African chimps, they are sometimes killed for meat. This is uncommon in Senegal, where eating chimpanzee meat is a taboo. But this isn’t the case in other West African countries, where researchers might see a bigger difference in chimp populations inside and outside protected areas. The researchers say that National parks could be especially effective at protecting chimps in these nations.

The difference in the number of species of carnivores and hooved animals (known as ungulates), inside and outside the park was stark — their populations were 14 and 42 percent higher in the park, respectively. This is in sharp contrast with what Lindshield was hearing on the ground in Senegal: There’s nothing in the park; all the animals are gone.

“There were qualitative and quantitative differences between what people were telling me and what I was seeing in the park,” she said. “Niokolo-Koba National Park is huge, and the area we study is nestled deeply in the interior where it’s difficult for humans to access. As a consequence, we see a lot of animals there.”

Hunting practices and human-carnivore conflict are two big reasons for ungulates thriving inside the park. These animals are frequently targeted by hunters, and some carnivore species turn to livestock as a food source when their prey species are dwindling, creating the potential for conflict with humans. Because the two sites are relatively close geographically and have similar grassland, woodland and forest cover, the researchers think human activity is the root of differences between the two sites.

Lindshield’s team conducted basic field surveys by walking around the two sites and recording the animals they saw. They also installed camera traps at key water sources, gallery forests and caves to record more rare and nocturnal animals.

“We’re engaging in basic research, but it’s crucial in an area that’s rapidly developing and home to an endangered species,” Lindshield said. “This provides evidence that the protected area is effective, at least where we are working, counter to what I was hearing from the public. The management of protected areas is highly complex. Myriad challenges can make management goals nearly impossible, such as funding shortfalls or lack of buy-in from local communities, but I think it’s important for people to recognize that this park is not a lost cause; it’s working as it’s intended to at Assirik, especially for large ungulates and carnivores.”

Lindshield hopes her future studies will uncover not only which species exist in each site, but population sizes of each species. This metric, known as species evenness, is a key measure of biodiversity.

Data from the unprotected area in Senegal was collected by Jill Pruetz of Texas State University. Stephanie Bogart and Papa Ibnou Ndiaye of the University of Florida, and Mallé Gueye of Niokolo-Koba National Park, also contributed to this research. Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation, National Geographic Society, Leakey Foundation, Rufford Foundation, Primate Conservation Inc., Jane Goodall Research Center at the University of Southern California, Purdue and Iowa State University.

Journal Reference:

Stacy Lindshield, Stephanie L. Bogart, Mallé Gueye, Papa Ibnou Ndiaye, Jill D. Pruetz. Informing Protection Efforts for Critically Endangered Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) and Sympatric Mammals amidst Rapid Growth of Extractive Industries in Senegal. Folia Primatologica, 2019; 124 DOI: 10.1159/000496145

Materials provided by Purdue University. Originally written by Kayla Zacharias.