From the Field

Deming Yang is a PhD candidate from Stony Brook University. He was awarded a Leakey Foundation Research Grant during our spring 2017 cycle for his project entitled “Isotopic variability among Plio-Pleistocene Turkana suids: Paleoenvironments and hominin evolution.” This is an update on his recent field research. You can read more about his research here.

I have recently returned from my data collection trips to the Turkana Basin in northern Kenya and Salt Lake City, Utah, with support from The Leakey Foundation. One of the questions my dissertation research project hopes to address is how the paleoenvironments in the Turkana Basin varied across space and time.

In eastern Africa today, vegetation composition within an ecosystem is largely determined by two factors. One is how much rain is available and the other is how rainfall is distributed throughout the year. A great example is the savanna ecosystem, which incorporates a wide range of habitats from grasslands to woodlands. The savanna is characterized by having low annual rainfalls, but with highly seasonal rains.

Typically, there are two rainy seasons a year in eastern Africa. The local communities have been relying on the rainy seasons to plan their agricultural activities. However, with climate change being a more prominent issue in the 21st century, the rains have become less predictable. This has profound influences on socio-economic dynamics and human-wildlife conflict in the region. But what were the rainy seasons like when our ancestors were evolving and developing new technologies?

To answer these questions, I am examining evidence from the early Pleistocene deposits in eastern Africa. My data collection started in the field with fossils. The most intensive field season for me was the Summer of 2018, during which I collected specimens from the Koobi Fora Formation on the eastern side of Lake Turkana. My field work was a bit different from more conventional field surveys in that it is built on the efforts of research teams who have worked in the areas over the past 10 years. During their previous surveys, the research teams had already located, photographed and identified many fossil specimens in the field, some of which were not collected owing to their poor preservation. With this information in hand, the first thing I did was to go through the specimen photos, select the fossils of interest and confirm their identification.

After the initial screening process, I then imported their latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates into my GPS device, so that I knew where I could find them in the field. However, nature works wonders with fossil deposits. Not only does it expose new fossils via erosion, but it also can wash away the ones that had been exposed! I found that among the specimens I attempted to locate in the field, about a third were missing from their original location and another third were not suitable for my project due to poor preservation. This was a valuable piece of information for me and perhaps other researchers who would like to employ similar methods in the future.

The time I spent in the field was relatively short, but there are always highlights. Walking into a field of sandstone blocks that were once at the bottom of a river was intriguing. It clearly demonstrates how tectonics and erosion shape the fossil deposits we know today. There were also outcrops that show transitions between coarse and fine-grain sediments in succession. That is because of the pulses of energy that flew through the basin at that time. Camping was entertaining, and we always had to improvise to some extent. We missed the hyenas who had visited us at the same camping ground in previous years.

My project involves sampling the fossil teeth for stable isotopes, a chemical analysis that can tell us something about what an animal ate and how often it drank. Another thing that is special about our teeth is that they are formed incrementally, like stalagmites. Therefore, if we take multiple samples from one tooth, we can get information about the diet and drinking behavior of the animal across a period of time (usually in the case of suids, at least a year).

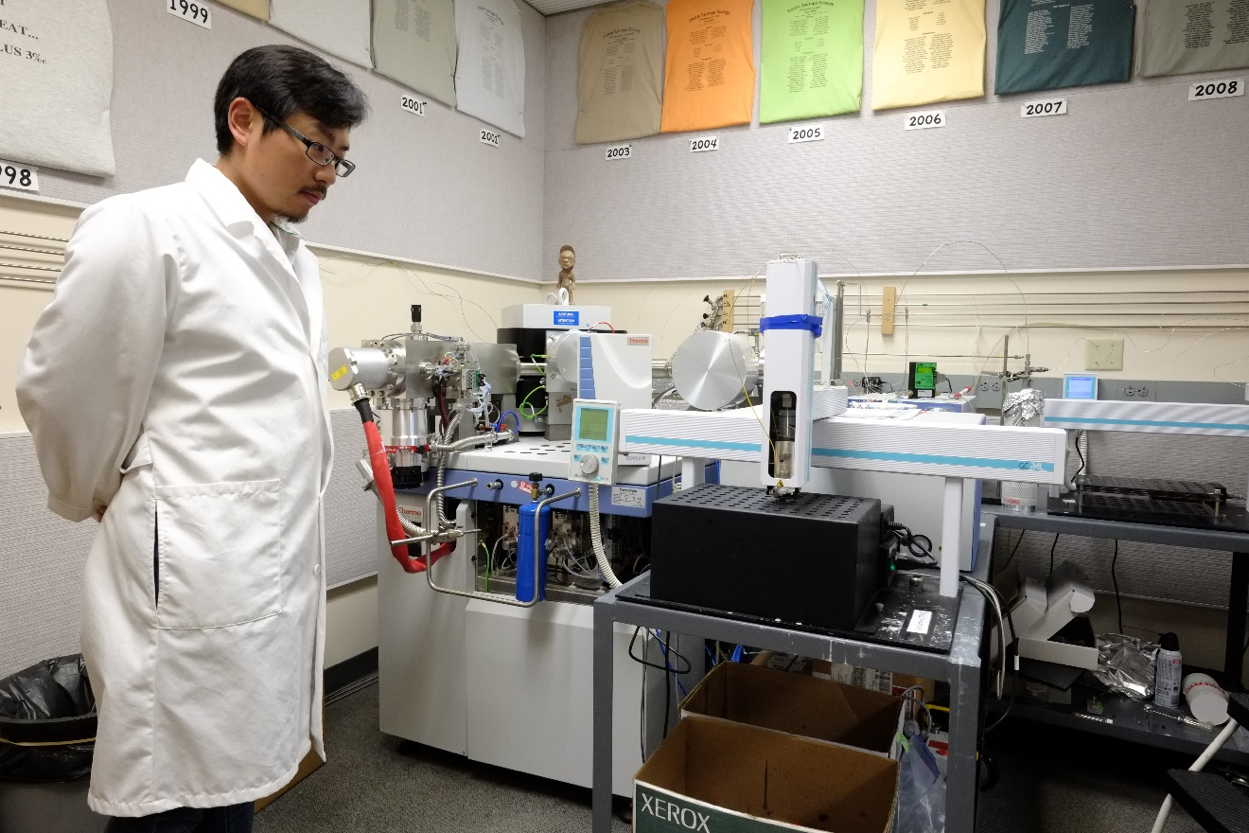

Since much of an animal’s diet and drinking behavior are determined by rainfall seasonality, we are learning about the seasonality of the past through the lens of fossil teeth! This analysis has a lab component in which I participated as a visiting student at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. The research methodology has advanced so much that we could make 130 measurements in one week! This was very efficient compared to perhaps 10 or 20 years ago. While the machines were doing most of the hard work for me, the most time-consuming part of the lab work was sample preparation and weighing.

I hope my analyses will provide some of the critical details of relevance to paleoenvironmental studies with a focus on human evolution. In summary, what I do is field work, lab work and then more lab work, producing data that will help inform us of past environments and seasonality in the Turkana Basin. Currently, I am back in New York doing data analysis for my dissertation. As I was typing these words, it was snowing outside. And I really missed the sunshine and desert roses in the field!