Journal Article

DURHAM, N.C. — Numerous studies have shown that childhood trauma can have far-reaching effects on adult health and survival; new research finds the same is true for wild baboons.

People who experience childhood abuse, neglect and other hallmarks of a rough childhood are more likely to develop heart disease, diabetes and other health problems later in life, even after the stressful events have passed, previous research shows.

A new study supported by The Leakey Foundation finds that wild baboons that experience multiple misfortunes during the first years of life, such as drought or the loss of their mother, grow up to live much shorter adult lives. Their life expectancy is cut short by up to ten years compared with their more fortunate peers.

The results are important because they show that early adversity can have long-term negative effects on survival even in the absence of factors commonly evoked to explain similar patterns in humans, such as differences in smoking, drinking or medical care, said Jenny Tung, an assistant professor of evolutionary anthropology and biology at Duke who co-authored the study.

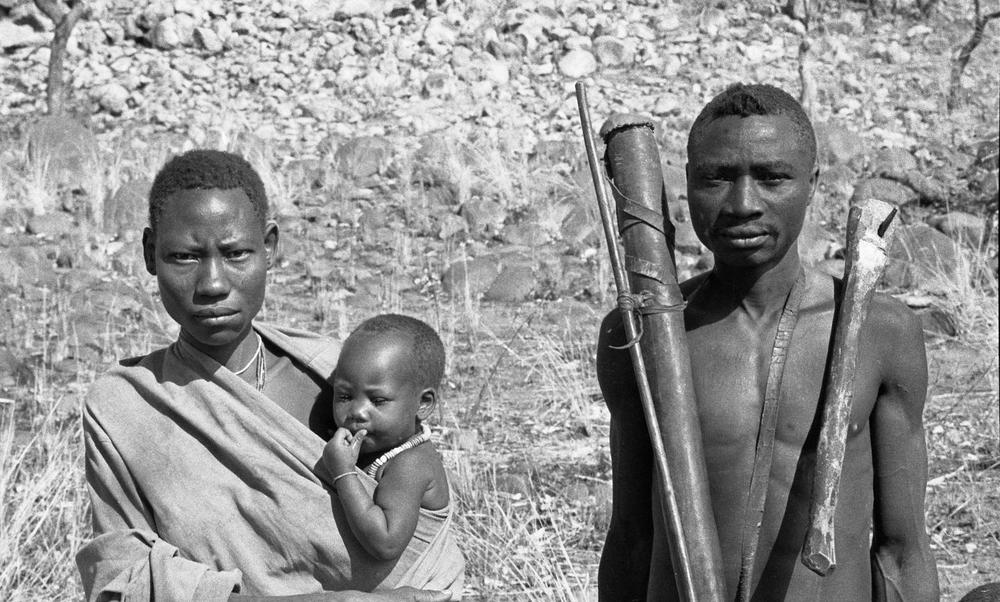

The findings, which were published online April 19th in Nature Communications, come from a long-term study of 196 wild female baboons monitored on a nearly daily basis between 1983 and 2013 near Amboseli National Park in southern Kenya.

Life isn’t easy for a wild baboon. Like many animals on the African savanna, baboons endure drought, overcrowding, disease and predation.

The researchers focused on six potential sources of early adversity. Some baboons, for example, saw very little rainfall in their first year of life, or experienced stiff competition for resources because of sibling spacing or rising numbers within their group. Others lost their mothers to death or illness, or had moms with lower rank or little social support.

More than three-fourths of the baboons in the study had at least one of the six early risk factors; 15 percent had three or more.

Baboons who lost their mothers before age four, or whose next-born sibling arrived before they were fully weaned, were found to be the most vulnerable.

For baboons, like humans, the tougher the childhood, the higher the risks of premature death later in life. Young females that experienced just one or no adverse events — a group the researchers nicknamed the “silver spoon kids” — generally lived into their late teens and early twenties, whereas those that endured three or more often died by age nine.

The “bad luck” babies not only lost more than ten years off their adult lives, they also had fewer surviving offspring. “It’s like a snowball effect,” said co-author Elizabeth Archie, associate professor at the University of Notre Dame.

Two females named Puma and Mystery, for example, were both born during years of little rainfall, and raised by low-ranking moms who died before their third birthdays. Puma eventually met her end at age seven at the jaws of a leopard. Mystery lived until her disappearance at age 14, presumably to a predator, leaving behind a single infant who died shortly thereafter.

Some researchers studying the effects of childhood stress on adult health in humans pin the blame on differences in medical care or risky behavior. People who had troubled childhoods, the thinking goes, are more likely to turn to drugs, alcohol or other coping mechanisms that are bad for their health.

But wild baboons don’t smoke or binge on junk food, and they don’t carry health insurance. This supports the idea that differences in lifestyle and medical care are only part of the story, said co-author Susan Alberts, professor of biology at Duke.

Baboon females that experienced the most misfortune in their early years were also more socially isolated as adults, suggesting that social support may also be at play.

Together with study co-author Jeanne Altmann of Princeton, the team plans to investigate how some baboons manage to overcome early adversity. It could be that those who form and maintain supportive relationships as they grow older are better able to survive and thrive, Archie said.

Baboon DNA is 94 percent similar to that of humans, which indicates these patterns could be deep-rooted in primate physiology, the researchers say. “This suggests that human adult health effects from childhood stresses are not simply products of the modern environment, but have likely been present throughout our evolutionary history,” says George Gilchrist, program director in the National Science Foundation (NSF)’s Division of Environmental Biology.

This research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health. Funding for the project has also been provided by The Leakey Foundation, Duke University, Princeton University, the Chicago Zoological Society, the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research and the National Geographic Society.