Uncategorized

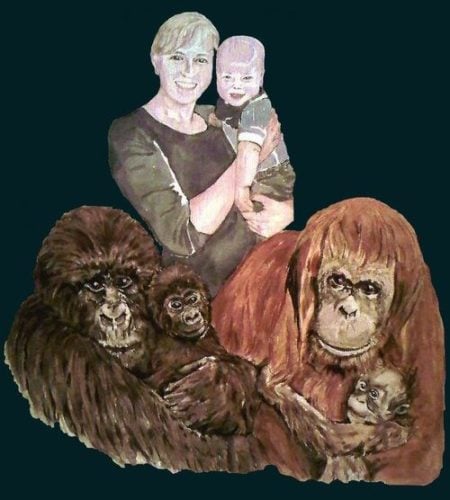

Image courtesy of Anne-Elise Martin

Throughout my career, one of my greatest rewards has come from interacting with generations of students. Their fresh, inquisitive minds have continually kept me on my toes. Countless times, I have been stopped in my tracks by smart, unexpected questions that sent me scurrying back to the drawing-board. But I must admit to feeling some dismay when, several years ago, one particular student came up to me at the end of a course and said: “I really enjoyed your lectures about primate evolution, but what is the point?” Well, as a rule my justification for what I do has been to say that studying the evolution of primates—and of humans in particular—is really just like tracing our written history. I simply go much farther back in time. Just as we are keenly interested in recorded history for its own sake, surely we should be interested in our deep biological history as well? But that student made me realize that I do have an obligation to show that understanding human evolutionary history can yield direct practical benefits. And that prompted me to get my act together and finally write my long-planned book for a general readership on the evolution of human reproduction. So I guess I owe a special acknowledgment to that student now that my book How We Do It: The Evolution and Future of Human Reproduction is about to be published.

One crucial point is that suckling is a defining feature of mammals. Indeed, their very name reflects this; it is derived from the Latin mamma for teat. Mothering began 200 million years ago when the first mammals emerged and it was further refined to become a particular hallmark of ancestral primates by 80 million years ago. Now a biological adaptation with that kind of pedigree should surely command our respect! Yet many people today are confused about what is “natural” for human mothers because cultural influences are so overwhelming. It is no exaggeration to say we have lost our way in certain respects. Unfortunately, in the industrialized world, male members of the medical profession were only too willing to offer guidance. They readily provided advice for mothers, absent any understanding of our evolutionary past. Thus it was that decades ago mothers were told to breastfeed their infants following rigid timetables and to avoid any kind of “pampering”. Thankfully, things have gradually moved away from those rigid guidelines. But how are we to know that this is not just a shift in fashion? Well, we know for sure that modern guidelines are more in tune with our biology. For instance, there is a major difference between mammals that suckle on schedule, as decided by the mother, and mammals that suckle on demand in response to the infant’s needs. And we can identify the adaptation of any mammal from milk composition. Mammals that suckle on schedule produce milk that is rich in fat and protein but poor in sugar, whereas mammals that suckle on demand have milk with relatively little fat and protein but a fair amount of sugar. For instance, all primates have that kind of milk because suckling on demand is a universal feature. And humans are no exception. The composition of human milk carries a signature that clearly tells us that we are biologically adapted for frequent suckling in response to the infant’s needs.

Another key question that we need to ask because cultural influences are now so overwhelming is “What is the natural duration of breastfeeding?” This question can be answered in different ways, and they all lead to virtually the same answer. We can, for instance, look at what other primates do. As you might expect, the duration of suckling is longer in larger-bodied primates, so we have to take body size into account. When that is done, the prediction is that a primate with our body size should suckle for about three years. We can also gather information from non-industrial societies, and one study of about a hundred different populations revealed that the average duration of breastfeeding is more than two-and-a-half years. This is also true of earlier human populations. Ancient Egyptian texts, for instance, indicate that breastfeeding for three years was the norm. Indeed, we can even extract information from earlier populations for which no historical records exist. By measuring stable isotopes in skeletons from young individuals, it is possible to tell when weaning occurred, and it was between two and three years of age in populations dating back thousands of years. These and other lines of evidence indicate that the natural duration of breastfeeding in our gathering-and-hunting ancestors was three years or perhaps even more.

Now two things must be emphasized straight away. The first is that exclusive breastfeeding, with no other source of food for the baby, last only six months or so. Complementary foods are provided in addition to the mother’s milk for much of that three-year period. Secondly, it has to be accepted that breastfeeding for three years is not practically possible for many modern mothers and that, for medical reasons, some are unable to breastfeed at all. So the point here is not to dictate a return to our gathering-and-hunting origins but to ensure that any substitute for breastfeeding meets all of the baby’s needs. And in that respect the biological evidence tells us that we still have a long way to go. For instance, in addition to providing nutrients, mother’s milk includes agents that protect the baby against infection until its own immune system is up and running. Bottle-fed babies suffer significantly more from various infections. There is also a large body of evidence indicating that breastfed babies have a small but statistically significant advantage over bottle-fed babies in the development of the brain. For instance, results on tests of mental performance are consistently a few points higher with breastfeeding, at least in part because certain essential fatty acids are more prevalent in human milk than in standard infant formula.

But it is not just the baby that benefits from breastfeeding. The mother benefits as well. Benefits start right after birth when stimulation of the mother’s nipples speeds up the recovery of the womb after the demands of pregnancy and birth. More seriously, various reproductive cancers occur at higher frequencies in women that breastfeed only for short periods or not at all. This is true not just of breast cancer but also of cancers of the ovaries and the womb. Once again, the take-home message is not that women should be obliged to breastfeed for long periods, but that we need to study our biological adaptations to find ways of offsetting any negative effects arising from modern lifestyles.

So, if that one-time student happens to read this, I hope that the point of studying human origins is now fully apparent.

Dr. Robert Martin

Dr. Robert Martin is A. Watson Armour III Curator of Biological Anthropology at the Field Museum in Chicago. He has devoted his career to exploring the evolutionary tree of primates, as summarized in his 1990 textbook Primate Origins. Martin is particularly interested in reproductive biology and the brain, because these systems have been of special importance in primate evolution. His research is based on broad comparisons across primates, covering reproduction,anatomy, behaviour, palaeontology and molecular evolution. He has written a new book How We Do It: The Evolution and Future of Human Reproduction, which is due to be published in June 2013.