Being Human | Guest Post

Guest blogger Rebecca O’Neill (see bio below) shares her impressions of our June 21st installment of Being Human. Join us for Being Human: Born and Evolved to Run on July 28th. Tickets are available at Ticketfly.com.

The Mona Lisa’s smile has intrigued countless viewers, from art historians to the average tourist walking past it in the Louvre. One moment, she seems to be smiling but then, as your eyes move around the canvas, the smile seems to wane. What is the secret behind this enigma?

Dr Margaret Livingstone, Professor of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School, has figured it

out. It has to do with the way our brains work, more specifically, with how our eyes collect the information and how we interpret that information in our visual cortex.

At a recent Being Human event at San Francisco’s Public Works, Margaret explained that our central vision is better at more precise information gathering while our peripheral vision is better at seeing larger objects. That’s why when you look at a page, you can’t read all the text on it at once – your eyes need to focus in on the text one line at a time to be able to recognize the words.

In the case of the Mona Lisa, if you were to look at the entire painting with your central vision, you’d get a very tight image, with everything in detail, but if you looked at the entire painting with just your peripheral vision, her features are blurry. In the central version, she doesn’t look like she’s smiling very much at all, whereas in the peripheral version, her grin looks like it stretches from ear to ear. In other words, when you look at the painting, your brain is receiving contradicting signals so it is challenging to define her expression.

In addition to the Mona Lisa example, Margaret walked us through a wide range of visual experiences and explained what each demonstrated in terms of our vision.

She told us that a whopping 25% of our brain is dedicated to processing vision. Within that 25%, humans have different areas that specialize in analyzing different aspects of images. For instance, one of the oldest parts of our brain (evolutionarily) is focused on more basic visual information such as depth and motion. Margaret stressed the importance of luminance (how light or dark something is) for those more ancient processes.

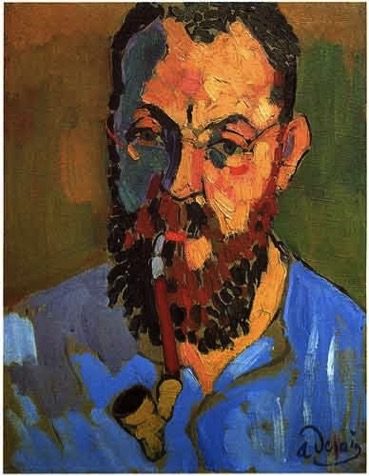

André Derain’s portrait of Henri Matisse is an example of this. At first glance, his use of greens and purples strikes you as jarring but yet, it actually works – you can still make out the contours of his face. That’s because of luminance (or what artists call value) – the greens and purples are darker than the yellows and peaches so register as further away/and or in shadow.

Humans have a more recently evolved part of their brain that is dedicated to deciphering objects. Only other primates share this section. Arguably, the most important object for us (and primates) is the face. In fact, Margaret explained that our face recognition system works by assessing how much the face in front of us deviates from an average face.

Picasso’s portraits exemplify this. Margaret argued that his paintings are like caricatures – he accentuated the sitter’s most striking features, such as a large nose or in his self-portraits, his large eyes.

I personally found the insights fascinating – I am a painter in my spare time and love using color. I will be applying my new knowledge next time I get my brushes out, for example, experimenting with how my eyes interpret a color when it is adjacent to varying colors on the canvas. Choosing to paint a red next to a green may make all the difference to the “mood” of the painting (thanks to them being “complementary” colors – opposite each other on the color wheel).

It turns out that I was joined at the event by many other artists and, in the Q&A part of the event, someone asked Margaret: why do humans make art? Her answer was simple: “We’re social animals – art is communication.”

Artists challenge us all to look at things differently. They convey raw emotion, political ideologies, religious beliefs, aesthetic ideals and much more through their visual representations of the world. It’s up to the viewer (and their highly evolved brain) to decide what to think about it.

About Rebecca O’Neill

I am a lifelong learner who is a passionate advocate for science and the human capacity for innovation. I have a Bachelors Degree in biology from Oxford University and a Masters Degree in environmental science from Imperial College London. I have worked in a variety of nonprofit, media and business roles to promote environmental conservation. I currently live in Oakland, California and work at SustainAbility, a hybrid think tank and strategic advisory firm working to catalyze business leadership on sustainability.

I am a lifelong learner who is a passionate advocate for science and the human capacity for innovation. I have a Bachelors Degree in biology from Oxford University and a Masters Degree in environmental science from Imperial College London. I have worked in a variety of nonprofit, media and business roles to promote environmental conservation. I currently live in Oakland, California and work at SustainAbility, a hybrid think tank and strategic advisory firm working to catalyze business leadership on sustainability.

Charles Darwin has been a hero of mine for as long as I can remember. Evolution is one of the most important scientific theories that humans have discovered. I believe that The Leakey Foundation’s mission is a crucial one – we need to understand how we have evolved in order to make better decisions for ourselves, our society and our planet, both now and in the future.