Today in History

By Dr. John Mitani

Professor Emeritus, University of Michigan

Co-founder, Ngogo Chimpanzee Project

Emeritus Member, The Leakey Foundation Scientific Executive Committee

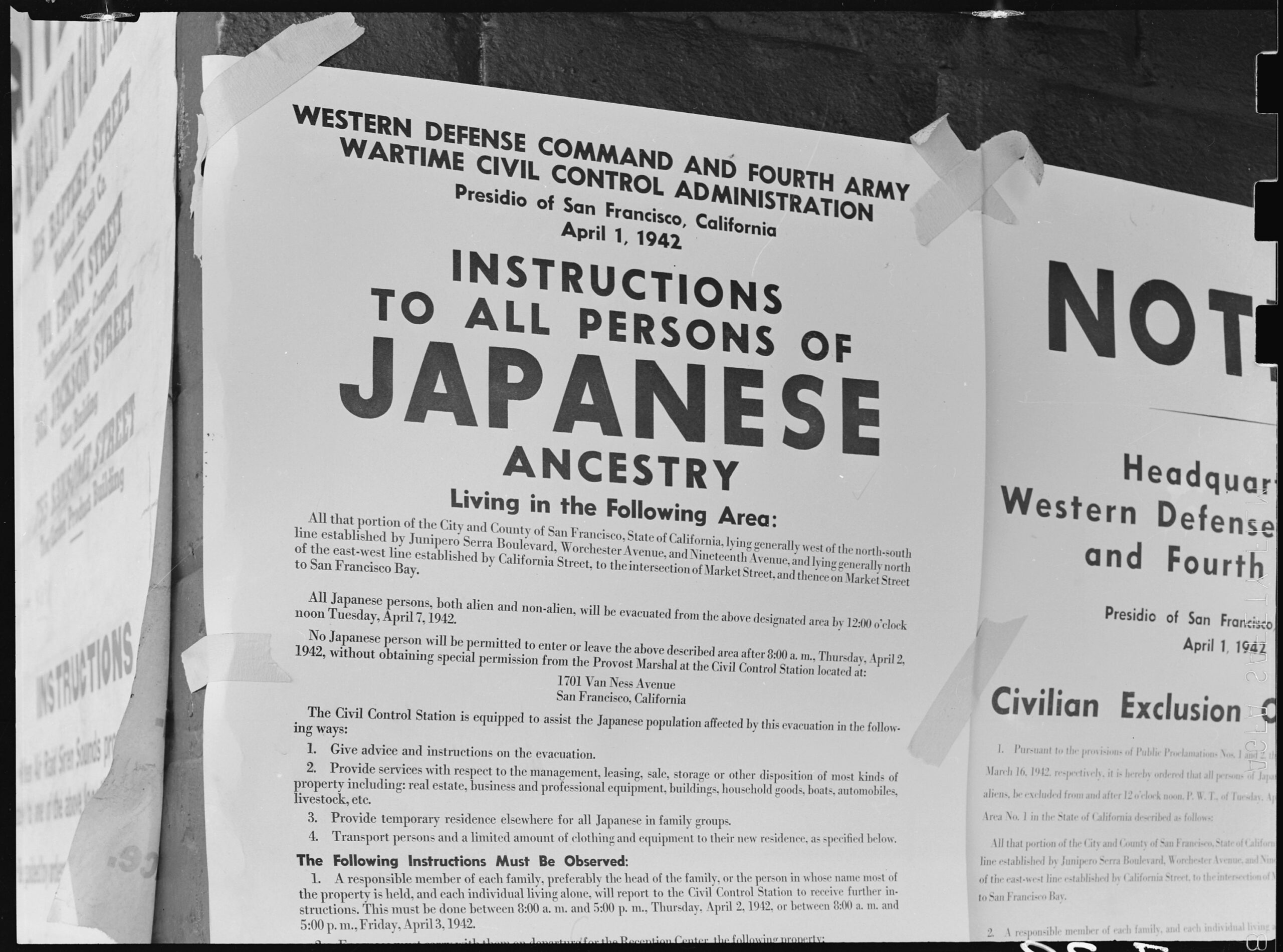

Today marks the anniversary of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signing Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942.

Some readers may be unfamiliar with this directive and its far-reaching consequences. The day after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt asked Congress for a declaration of war. In the weeks that followed, mass hysteria swept the country, and suspicion quickly fell on Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. Executive Order 9066, implemented a few months later, authorized the forced removal and incarceration of over 120,000 people of Japanese descent. Among them were native-born American citizens, including my parents, Don Kiyoshi Mitani and Sally Sadako Mitani, née Oshita. For over three years, families like mine lived in “relocation centers” in remote and desolate areas far from public scrutiny.

This imprisonment of law-abiding citizens and immigrants was an unprecedented chapter in American history. My parents and thousands of others were not charged with crimes. Nevertheless, they were forcibly uprooted, stripped of their homes, possessions, and businesses. No one was given the right to defend themselves in a court of law nor was anyone compensated for the seizure of their property. And the order was applied nearly exclusively to people of Japanese descent. Today those actions are widely recognized as violating the fundamental constitutional guarantees of due process, just compensation, and equal protection of the laws.

Few objected at the time. In fact, most supported the policy of mass incarceration and readily accepted the assertions of political leaders who deemed it necessary for national security in the absence of any evidence that these people represented a threat. Earl Warren, California’s Attorney General, was among the most vocal proponents. Roosevelt, Warren, and others invoked the now familiar Alien Enemies Act of 1798, ignoring a Naval Intelligence report that concluded Japanese Americans did not pose a security risk (see: Ringle Report on Japanese Internment).

What followed was a story of human survival seldom told, and for me, never fully explained. This is because my parents remained reluctant to talk about their experience. Growing up, I accepted their silence and rarely asked questions. Years later I realized their reticence was due to an abiding pain and a facet of Japanese culture embodied in the expression, “shikata ga nai,” meaning “nothing can be done.” Many who were incarcerated accepted their fate as something beyond their control and moved on to make the best of a bad situation.

The rare times my parents discussed their imprisonment were unforgettable. In February 1942, my mother was a senior at Salinas High School hoping to graduate with her classmates. Instead, she and her family spent the next few months at the Salinas rodeo grounds. In the rush to incarcerate so many people, the government relied on temporary “assembly centers” like this before moving them to the aforementioned relocation centers. My mother lived in a hastily constructed wooden barrack cramped together with many others.

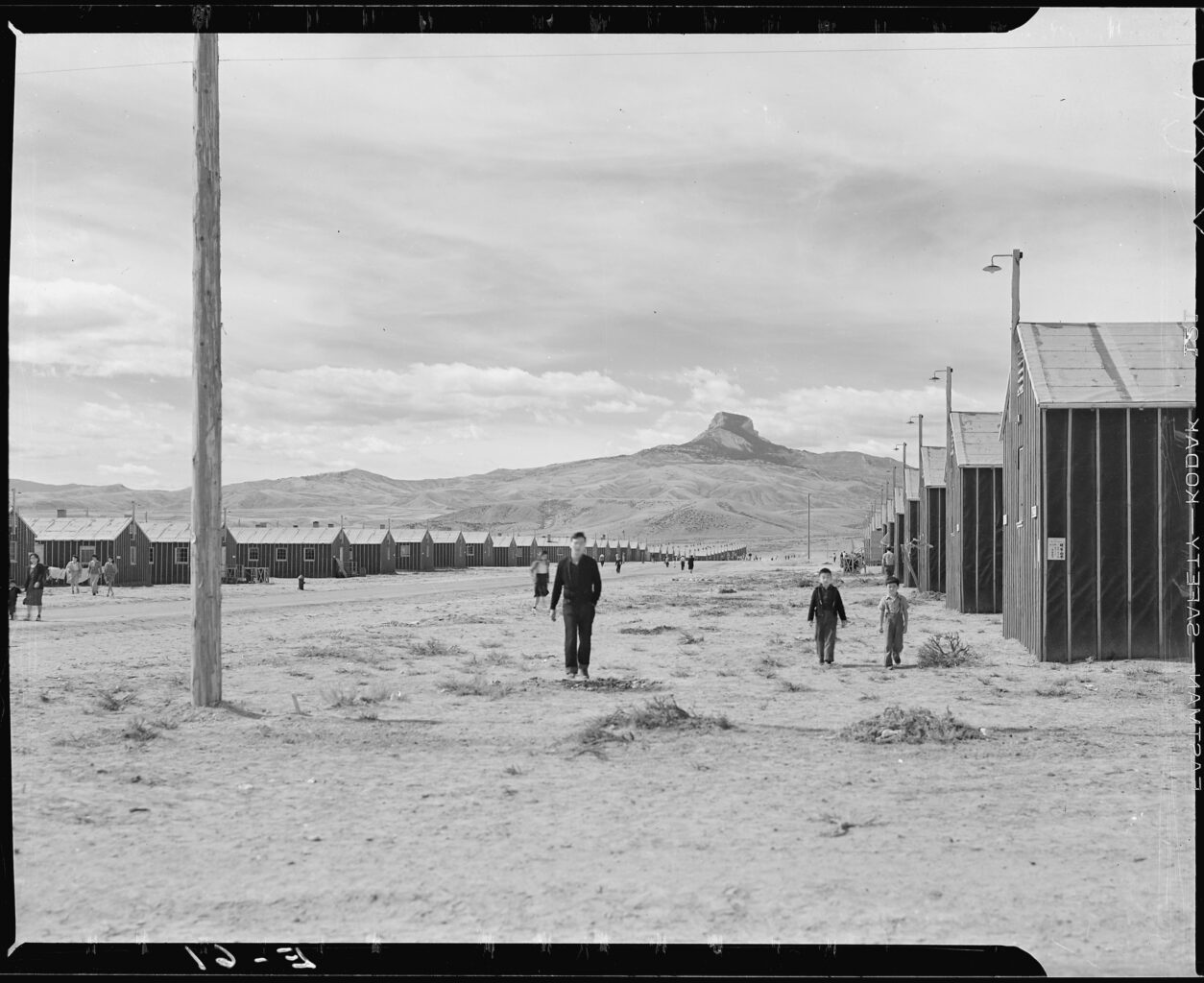

Poston, Arizona. A War Relocation Authority representative gives instructions and assignments to imprisoned people outside of a tar paper shack at the Poston camp.

Francis Stewart, National Archives

She was subsequently sent to Poston in the Arizona desert where she was housed in a tar-paper shack. I remember her describing the oppressive summer heat, the winter cold, and the scant privacy provided by communal bathrooms with no plumbing. Photographs she kept revealed cabins with thin walls, lacking proper insulation and ill-equipped for the harsh desert climate.

My father fared no better. Following a brief incarceration at Tule Lake in California, he spent the rest of the war at Heart Mountain in Wyoming. He spoke little about his time there but would occasionally recount the brutal winters, bleak landscape, and barbed wire fences guarded by armed soldiers. His stoicism and silence reflected a quiet strength displayed by many who were imprisoned.

I never pressed my parents to share more, and now after their passing, I am left with questions that will never be answered. What was daily life like? How did they find ways to keep hope alive? Despite their silence, I remain deeply grateful for the resilience they showed in the years that followed.

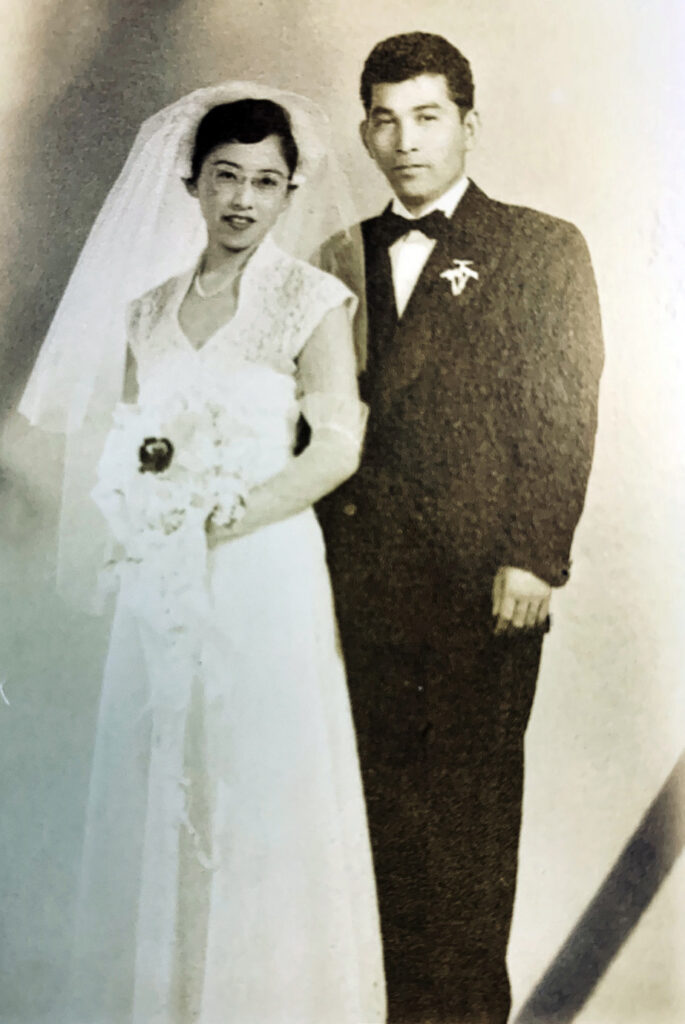

When the war ended, incarcerees were released, given just $20, and told to leave. My parents never described how they felt or what plans they had at the time. They subsequently met in Los Angeles, married, and moved to Northern California, where my two brothers and I grew up largely unaware of the details of what they had endured. They did not dwell on the past. Instead, shikata ga nai gave way to action. They focused on what they could do by building a new life and providing for their family with hard work and steely determination. I am the beneficiary of this, as my parents did everything in their power to ensure that my brothers and I were given opportunities that had been denied to them.

The relevance of this story endures. The same fear of people who look, speak, or act differently lives on in this country, echoing the irrational hysteria that led to my parents’ incarceration, with consequences disturbingly akin to and in some cases even more horrific than what happened to them. This fear of others is not exclusive to humans. Xenophobia plays a prominent role in the lives of our closest living relatives, chimpanzees. But we are not chimpanzees.

Research supported by the Leakey Foundation reveals that since we last shared a common ancestor with chimpanzees 6 – 8 million years ago, humans have evolved to become cognitively and culturally complex and unusually cooperative. It’s this last aspect of human behavior, our remarkable tendency to empathize and help others that is pertinent to this account of my parents’ wartime experience. Our extreme prosociality enables us to live together peaceably, with the kind of grace and humility displayed by my parents throughout their lives.

On this day of remembrance, I hope we will never forget the lessons of history. One important lesson is that our survival depends on a quintessential human trait: our ability to tear down instead of building walls among ourselves.

John Mitani is a primate behavioral ecologist who has investigated the behavior of our closest living relatives, the apes. His current research involves studies of two communities of wild chimpanzees in Uganda at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, and addresses questions regarding social relationships, territoriality, and lethal intergroup aggression. He has been the recipient of five Leakey Foundation grants and is an emeritus member of the Leakey Foundation’s Scientific Executive Committee.

The Leakey Foundation is best known for supporting research on human evolution and primate behavior, but its mission extends to public understanding of human origins, behavior, and survival. Dr. Mitani’s essay is a reminder that this science can illuminate both our capacity for cruelty and our remarkable ability to overcome it.

Resources to learn more:

Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority, 1942–1945

World War II Japanese American Incarceration: Researching an Individual or Family

Japanese Relocation and Internment, Archives Library Information Center (ALIC)

A collection of oral history interviews from the California Museum