Being Human

His Ideas Are a Linchpin of Modern Science

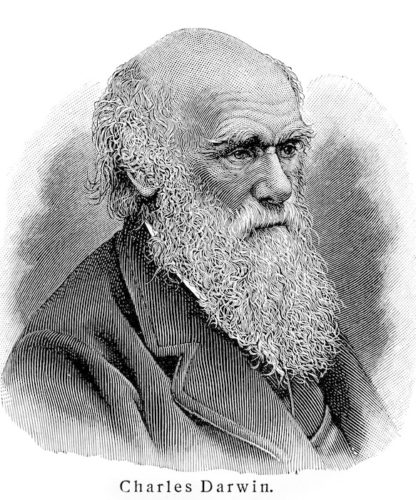

Charles Darwin is centrally important in the development of scientific and humanist ideas because he first made people aware of their place in the evolutionary process when the most powerful and intelligent form of life discovered how humanity had evolved. The theory of evolution by natural selection was first put forward by Darwin in On the Origin of Species, published in 1859, and his theory is still generally accepted as the best available explanation of the way life on this planet developed.

Darwin’s father was a country doctor in and around Shrewsbury, and the young Charles grew up in an extended family who knew the countryside and its pursuits well. His grandfather was Erasmus Darwin, an eminent naturalist and poet. As a boy he collected beetles, moths and other objects of curiosity, and he and his brother did simple chemistry experiments in the attic of their large house. He attended Shrewsbury School where he did not do particularly well – he was more interested in beetles than in Latin grammar. Neither was he a very successful university student. He was persuaded by his father to study medicine, but did not complete his medical studies at Edinburgh, because he found it “intolerably dull” and could not stand the sight of blood. So he went to Cambridge University to study theology, but here too there were more interesting pursuits than his studies. At Cambridge he met a prime mover in the developing science of Geology, Adam Sedgwick, whom he accompanied on field trips to North Wales and other places. He also met and learned a great deal from Professor Henslow, a wonderful teacher and friend, with whom he chased moths and butterflies across the fens with a big net, and learned to classify plants.

In 1830, when Darwin was only 22, Henslow learned of the imminent departure of a Royal Navy survey ship, HMS Beagle, which was in need of a naturalist. Would Charles like to go? Charles jumped at the opportunity. His father reluctantly gave permission, and the ship sailed from Plymouth on 27 December 1831. The main object was to make good naval charts of parts of South America, which was the speciality of Captain Fitzroy, who was also rather fundamentalist in his religious views. It was while they were surveying the Galapagos Islands that Darwin made many observations which eventually led to his theory of evolution by natural selection, although he barely grasped the significance at the time. “The natural history of these islands is eminently curious,” he wrote in his journal. And so it was: the ten rocky islands were home to many plants and animals that were like those of neighbouring South America , but with distinct differences. Half the species of birds living on these islands occurred nowhere else on the planet. Each island had its own species. How had this come about? Could this extraordinary variety really be explained by the idea that God had created all the species on Earth in six days? Could the variations he saw on the Galapagos have anything to do with the huge scale of geological time he had learnt about from geologists such as Sedgwick? In a tentative way, Darwin argued about these issues with Captain Fitzroy, whose dogmatic religious belief acted as a useful stimulant, though neither knew it at the time. Darwin thought that the unique species of the Galapagos could not have been specially created for each island, but must have evolved from similar ancestors carried from the mainland and washed up on the islands. But how had this evolution occurred?