Journal Article

More than three million years ago, our ancient human ancestors, including their toddler-aged children, were standing on two feet and walking upright, according to a new open-access study published in Science Advances.

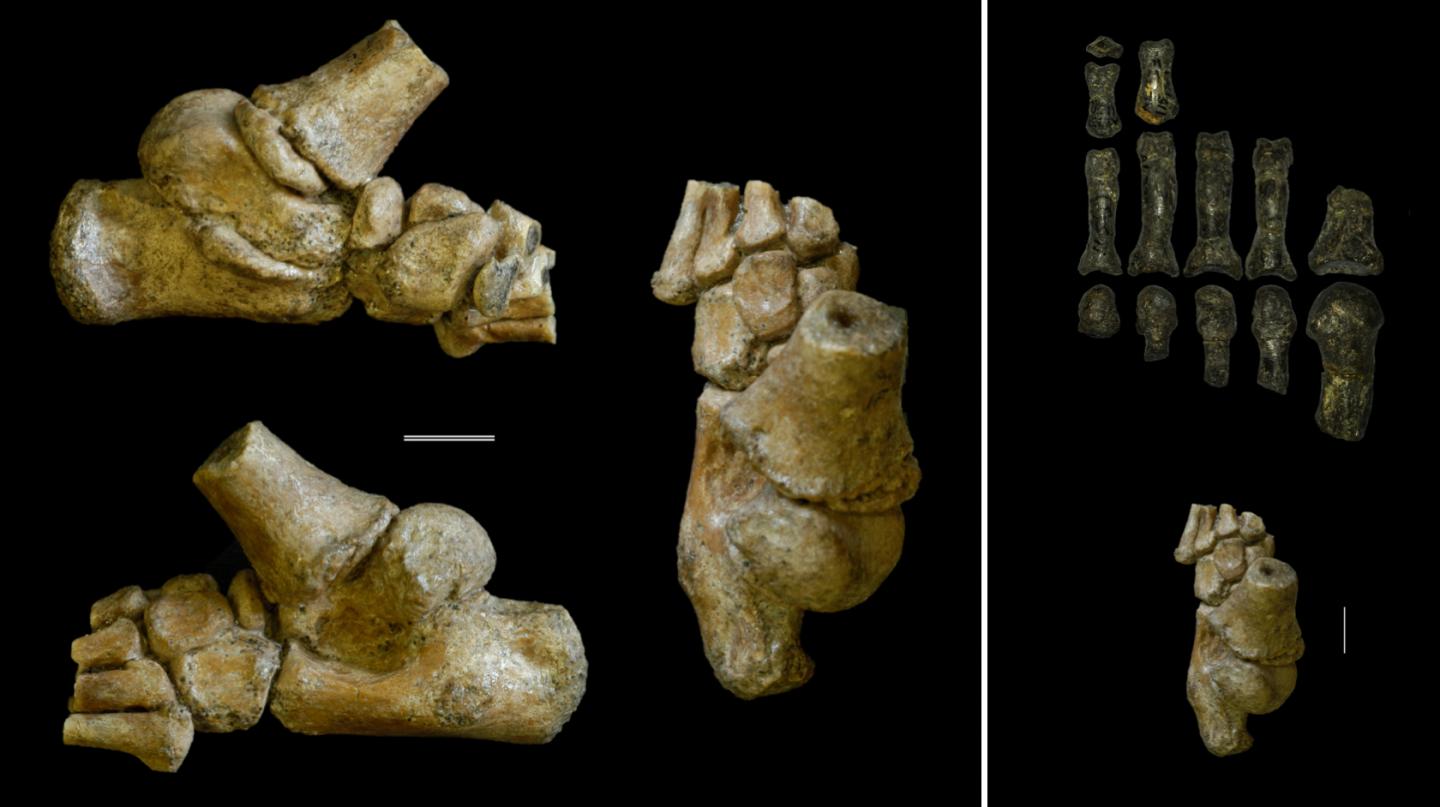

“For the first time, we have an amazing window into what walking was like for a 2½-year-old, more than three million years ago,” says lead author, Jeremy DeSilva, a Leakey Foundation grantee and associate professor of anthropology at Dartmouth College, “This is the most complete foot of an ancient juvenile ever discovered.”

The tiny foot, about the size of a human thumb, is part of a nearly complete 3.32-million-year-old skeleton of a young female Australopithecus afarensis discovered in 2002 in the Dikika region of Ethiopia by Leakey Foundation grantee Zeresenay (Zeray) Alemseged, a professor of organismal biology and anatomy at the University of Chicago and senior author of the study. This remarkable fossil skeleton is nicknamed Selam or ‘the Dikika child.’

In studying the fossil foot’s remarkably preserved anatomy, the research team strived to reconstruct what life would have been like for this toddler. They examined how it developed and what it tells us about human evolution. The fossil record indicates that these ancient hominins were quite good at walking on two legs. “Walking on two legs is a hallmark of being human. But, walking poorly in a landscape full of predators is a recipe for extinction,” explained DeSilva.

“Placed at a critical time and the cusp of being human, Australopithecus afarensis was more derived than Ardipithecus (a facultative biped) but not yet an obligate strider like Homo erectus. The Dikika foot adds to the wealth of knowledge on the mosaic nature of hominin skeletal evolution,” explained Alemseged.

At 2½ years old, the Dikika child was already walking on two legs, but there are hints in the fossil foot that she was still spending time in the trees, hanging on to her mother as she foraged for food. Based on the skeletal structure of the child’s foot, specifically, the base of the big toe, the research suggests that children probably spent more time in the trees than adults. “If you were living in Africa three million years ago without fire, without structures, and without any means of defense, you’d better be able to get up in a tree when the sun goes down,” said DeSilva. “These findings are critical for understanding the dietary and ecological adaptation of these species and are consistent with our previous research on other parts of the skeleton especially the shoulder blade,” Alemseged noted.

This article was written with materials provided by Dartmouth College.