Journal Article

A new Leakey Foundation-supported discovery helps date the transatlantic migration to about 34 million years ago, around the time a major drop in sea level would have made the ocean voyage shorter.

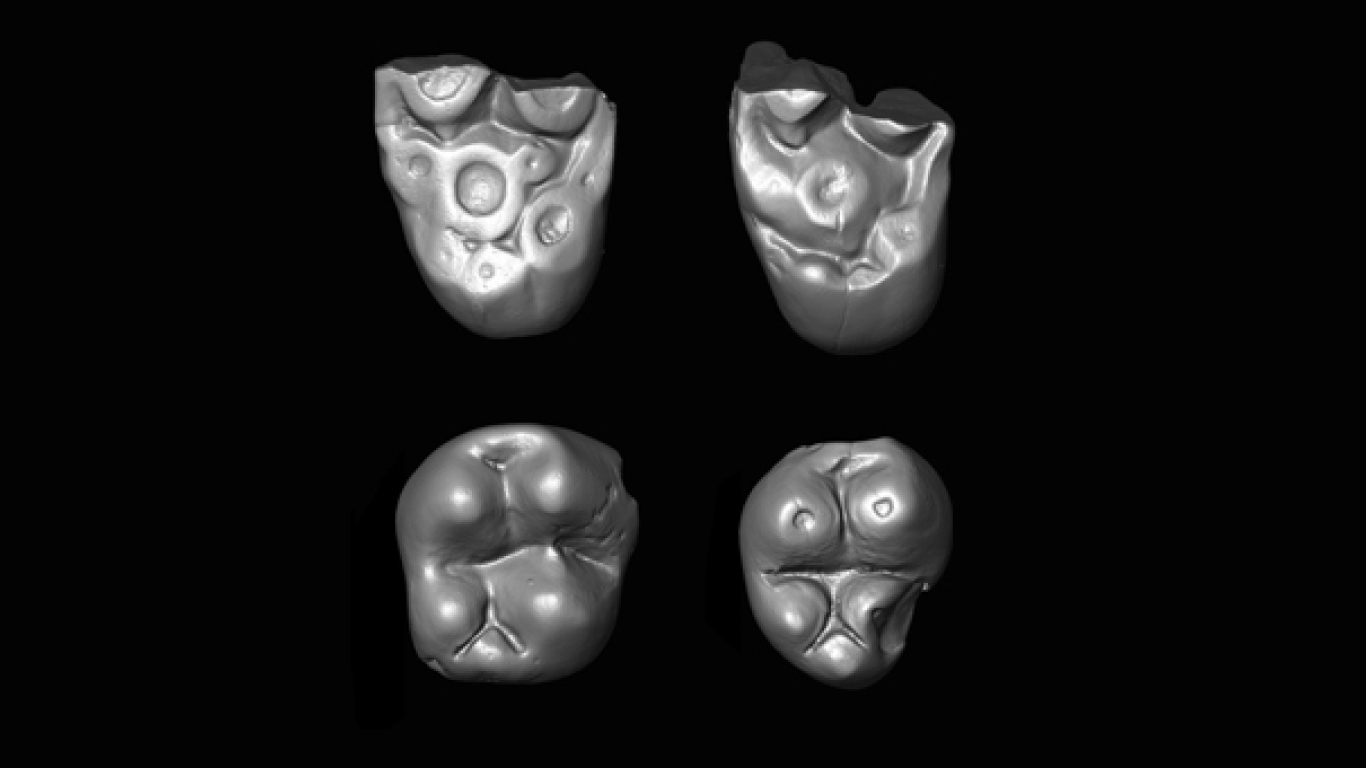

Four fossilized monkey teeth discovered deep in the Peruvian Amazon provide new evidence that more than one group of ancient primates journeyed across the Atlantic Ocean from Africa, according to new USC research just published in the journal Science.

The teeth are from a newly discovered species belonging to an extinct family of African primates known as parapithecids. Fossils discovered at the same site in Peru had earlier offered the first proof that South American monkeys evolved from African primates.

The monkeys are believed to have made the more than 900-mile trip on floating rafts of vegetation that broke off from coastlines, possibly during a storm.

“This is a completely unique discovery,“ said Erik Seiffert, the study’s lead author and Professor of Clinical Integrative Anatomical Sciences at Keck School of Medicine of USC. “It shows that in addition to the New World monkeys and a group of rodents known as caviomorphs – there is this third lineage of mammals that somehow made this very improbable trans-Atlantic journey to get from Africa to South America.”

Researchers have named the extinct monkey Ucayalipithecus perdita. The name comes from Ucayali, the area of the Peruvian Amazon where the teeth were found, pithikos, the Greek word for monkey and perdita, the Latin word for lost.

Ucayalipithecus perdita would have been very small, similar in size to a modern-day marmoset.

Dating the migration

Researchers believe the site in Ucayali where the teeth were found is from a geological epoch known as the Oligocene, which extended from about 34 million to 23 million years ago.

Based on the age of the site and the closeness of Ucayalipithecus to its fossil relatives from Egypt, researchers estimate the migration might have occurred around 34 million years ago.

“We’re suggesting that this group might have made it over to South America right around what we call the Eocene-Oligocene Boundary, a time period between two geological epochs, when the Antarctic ice sheet started to build up and the sea level fell,” said Seiffert. “That might have played a role in making it a bit easier for these primates to actually get across the Atlantic Ocean.”

An improbable discovery

Two of the Ucayalipithecus perdita teeth were identified by Argentinean co-authors of the study in 2015 showing that New World monkeys had African forebears. When Seiffert was asked to help describe these specimens in 2016, he noticed the similarity of the two broken upper molars to an extinct 32 million-year-old parapithecid monkey species from Egypt he had studied previously.

An expedition to the Peruvian fossil site in 2016 led to the discovery of two more teeth belonging to this new species. The resemblance of these additional lower teeth to those of the Egyptian monkey teeth confirmed to Seiffert that Ucayalipithecus was descended from African ancestors.

“The thing that strikes me about this study more than any other I’ve been involved in is just how improbable all of it is,” said Seiffert. “The fact that it’s this remote site in the middle of nowhere, that the chances of finding these pieces is extremely small, to the fact that we’re revealing this very improbable journey that was made by these early monkeys, it’s all quite remarkable.”

About this study

In addition to Seiffert, the study’s other authors are Marcelo Tejedor and Nelson Novo from the Instituto Patagónico de Geología y Paleontología (CCT CONICET – CENPAT); John G. Fleagle from the Department of Anatomical Sciences, Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook University; Fanny Cornejo and Dorien de Vries from the Interdepartmental Doctoral Program in Anthropological Sciences, Stony Brook University; Mariano Bond from CONICET, División Paleontología Vertebrados, Museo de Ciencias Naturales de La Plata and Kenneth E. Campbell Jr. from the Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

The study was supported by J. Wigmore, W. Rhodes, and R. Seaver, who helped to fund the 1998 expedition that led to the recovery of the Ucayalipithecus partial upper molars; The Leakey Foundation, Gordon Getty, and A. Stenger who supported the fieldwork in 2016; and the Keck School of Medicine of USC and the U.S. National Science Foundation (BCS-1231288) which supported micro-CT scanning.