Human Origins

New fossil discoveries reveal the surprising stature, locomotion, and behavior of Paranthropus robustus, a human relative that co-existed with our ancestors.

by Evan Hadingham

At the Cradle of Humankind near Johannesburg, South Africa, rarely preserved hip and leg bone fossils present fresh clues about Paranthropus robustus, a small-brained human relative with a rugged skull and massive chewing teeth that co-existed with our early Homo ancestors around 2 million years ago.

The discovery throws light on the much debated question of whether Paranthropus robustus was a habitual upright walker as well as a tree dweller. The strikingly small size of the fossil has implications for the species’ social structure and its vulnerability in a savannah teeming with fierce predators. The research was published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

Cave traps in the Cradle

The fossil bones came from Swartkrans, one of many collapsed limestone cave sites in the Cradle of Humankind revealed by the blasting activities of gold prospectors. The caves were not prehistoric dwelling places but natural traps into which rocks, debris, and skeletal remnants collected at the bottom of shafts and fissures in the rock. The debris was cemented into a hard cave sediment called breccia; eventually, most of the fossil bones incorporated in the breccia were compressed into small, unidentifiable fragments except for the most durable skeletal parts: skulls, jaws and teeth.

In 1938, a schoolboy found teeth and parts of a skull at Kromdrai Cave and showed them to paleontologist Robert Broom, who named the specimen Paranthropus robustus. It was notable for its massive jaws and thickly enameled teeth, with molars sometimes twice as big as ours. Huge chewing muscles enabled it to grind and chew hard, fibrous, low-quality foods, helping it to thrive in times of scarcity. The stone and bone tools found at many Paranthropus sites would have enabled it to vary its diet by digging for buried roots, tubers, and termites.

Secrets in the roof

In March 2019, University of Witwatersrand technician Lukas Sekowe noticed what looked like the top part of a fossilized femur, its front sliced off by mining activity and exposed at the end of a block of breccia. The block was one of a half-dozen that paleontologists had pried off a fossil-rich layer embedded under the roof of the Swartkrans cave. Painstaking work with hand-held compressed air drills eventually revealed a well-preserved hip, thigh and shinbone. They are the first articulating post-cranial remains of Paranthropus robustus ever discovered.

An international team affiliated with the University of Witwatersrand and led by Travis Pickering of the University of Wisconsin-Madison analyzed the bones by comparing them with the anatomy of other hominin species and present-day populations. This work, partly supported by The Leakey Foundation, confirmed that Paranthropus was a committed upright walker. Its lower limbs resemble those of modern humans rather than an ape-like tree climber, while the end of the tibia bone indicates the likely presence of an arched foot—another sign of developed upright walking.

Paranthropus robustus among the tiniest

On the basis of the limb bones, the team identified the fossil as a young adult and estimated that it was just 3.4 feet tall and weighed 60 pounds—among the tiniest human ancestors ever discovered. It was slightly shorter and lighter than either Lucy or the celebrated “hobbit,” LB1, discovered in Liang Bua cave in Flores, Indonesia, in 2003. Since some Paranthropus robustus specimens weigh almost double that of others, the evidence suggests that the species was sexually dimorphic, with males much larger than females. Among living primates such as gorillas, this disparity in size is typical of polygyny, in which a single dominant male mates with multiple females. On that basis, the team tentatively identified the Swartkrans specimen as female.

Surviving the predators

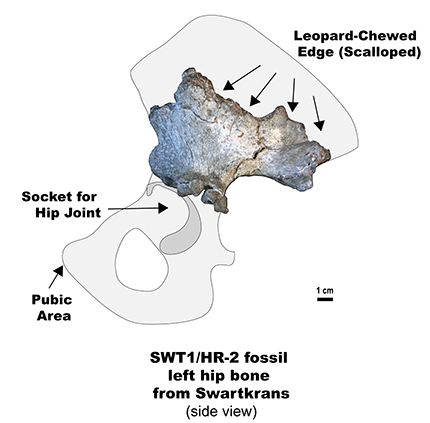

Its slightness and tiny stature would surely have made it easy prey for prowling predators like leopards, giant hyenas and saber-tooth cats. The lab team identified bite marks and tooth impressions on the hip and femur bones identical to those left by modern leopards. They also found a complete leopard skull in the same block of breccia that concealed the limb bones. The evidence is consistent with the “Swartkrans leopard hypothesis” first developed by leading South African paleoanthropologist C.K. Brain in the 1970’s, who sought to account for the frequent bite marks evident on fossils in several of the caves excavated in the Cradle of Humankind. Brain theorized that leopards would drag carcasses up into trees to consume them as they often do today. Leftover skeletal parts would tumble down from the trees or be swept into the limestone fissures below.

“Although it seems that this particular individual was the unfortunate victim of predation,” Travis Pickering says, “that conclusion does not mean that the entire species was inept. We know that Paranthropus robustus survived in South Africa for over one million years.” If it ultimately proved to be a dead end in the human story, Paranthropus testifies to a different yet remarkably successful survival strategy than that of its contemporaries—the ancestors who would lead to us.

Read the research

Travis Rayne Pickering, Marine Cazenave, R.J. Clarke, A.J. Heile, Matthew V. Caruana, Kathleen Kuman, Dominic Stratford, C.K. Brain, Jason L. Heaton.

First articulating os coxae, femur, and tibia of a small adult Paranthropus robustus from Member 1 (Hanging Remnant) of the Swartkrans Formation, South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution, Volume 201, 2025.

doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2024.103647

Love science like this? Help make it happen!

Double your impact on human origins research and education.

For a limited time, your one-time or monthly gift will be matched!