Education | From the Field

By Gus Dupin

Founded in 1996 by Dr. Eduardo Fernández-Duque, the Owl Monkey Project (OMP) is a multi-decade field study of wild owl monkeys (Aotus azarae) in the forests of Formosa, Argentina. The project combines research in population biology, demography, behavior, genetics, endocrinology, and ecology to investigate the roles of males and females in the evolution of pair-living, the maintenance of monogamy, and the dynamics of biparental care.

Over nearly three decades, and with the invaluable support of multiple funding agencies and partners, including The Leakey Foundation, the study of these small monkeys has enabled the project to generate key insights into the evolution of pair bonding, parental care, and primate life history, while also contributing to conservation in the South American Chaco region.

Notably, the very first grant ever awarded to Dr. Fernandez-Duque to start the Owl Monkey Project was from The Leakey Foundation, marking the beginning of a 30-year partnership. More recently, project co-director Dr. Alba García de la Chica also became a Leakey Foundation grantee, exemplifying the foundation’s commitment to supporting new generations of researchers and ensuring the continued growth and trajectory of the project.

A training ground for students and volunteers

Beyond research, the OMP has served as a training ground for more than 400 students and volunteers from 22 countries, many of whom have participated through grants linked to the project. Many arrived with little or no field experience, but through their time in the project, they developed hands-on skills and a deeper understanding of what fieldwork and living in the field entail. I was one of them, joining the OMP as part of a summer program.

When I was traveling to the field site, I wasn’t sure just what to expect. I knew I would be sleeping in a tent and going into the forest, but besides that, I couldn’t picture what it would be like. When I arrived, I immediately realized a lot of my preconceptions were pretty wrong. I was pleasantly surprised to learn that we had a stove to cook on and would not be building a fire for every meal.

Over my time there, I became familiar with all the oddities and aspects of the site. I tried to describe it to my friends and family, but despite my many descriptions and pictures, they continued to have little clue about what was going on. I think my mom only began to grasp my sleeping situation when I told her about a tarantula I found on my pillow before bed.

Minecraft as a way to share the field site experience

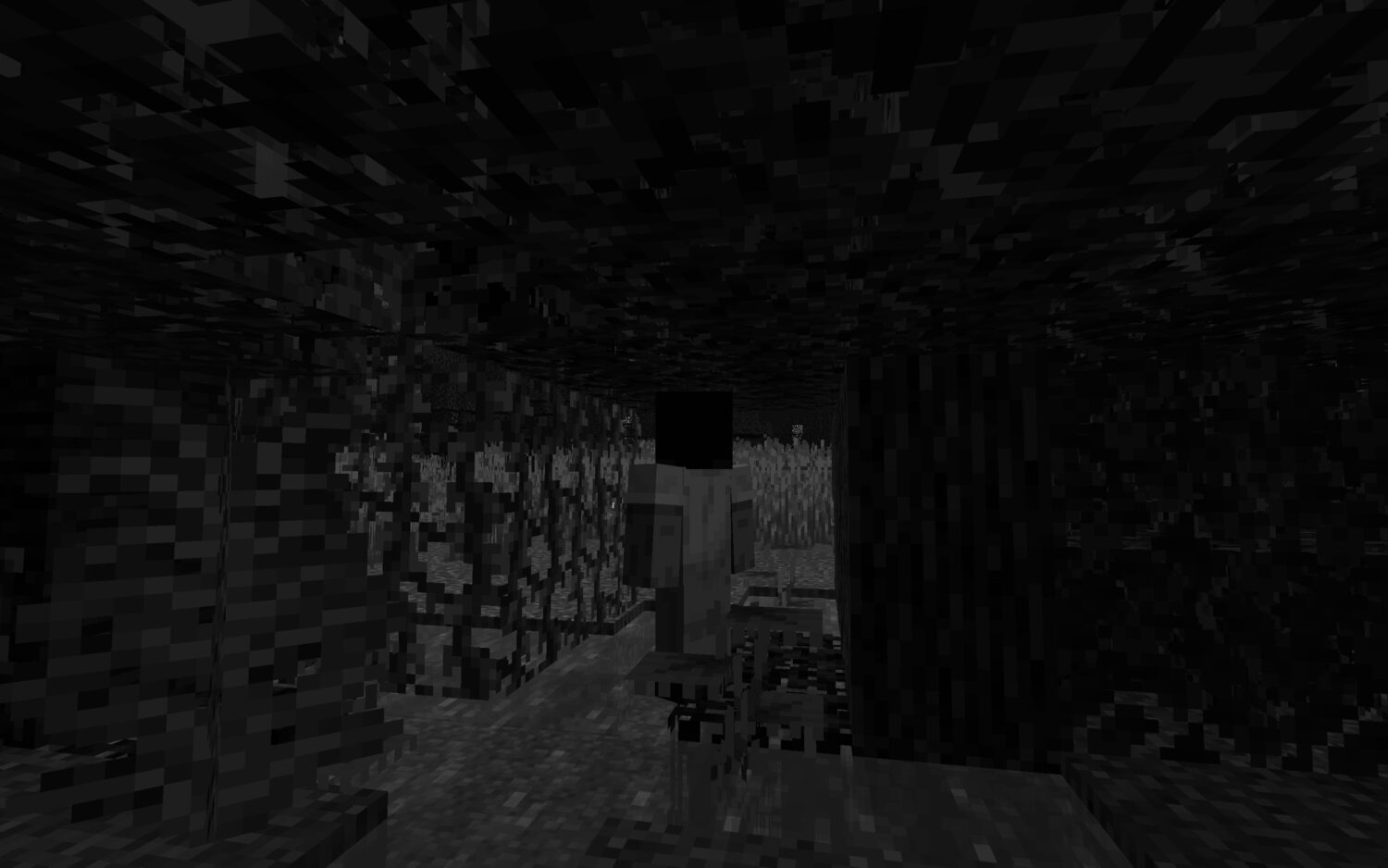

The vast majority of people, my family and friends included, don’t know what it’s like to be at a primate field site, or any type of field research site for that matter. So, I decided that a great way to show people, and a great way for me to remember the site, would be to build a replica of it in Minecraft. I’ve always loved Minecraft, and it’s a widely accessible and very popular game that’s perfect for building and immersing yourself in a whole new world.

I started off by finding an area in the randomly generated world that was somewhat similar to our site. Our camp sits right along a river inside a large cattle ranch, so I spent a long time looking for a large forest bordered by a vast open area and a body of water. Once I was happy with a spot, I got to work building our camp, adding tents (which I learned are quite hard to build in Minecraft), one of our trucks, and the “Quincho”, the main building in camp where we cooked, worked, hung out, and more.

Due to its multifunctionality, the Quincho is filled to the brim with everything we need. Equipment fills the few tables and shelves, food for the week is stored in boxes along the wall, cooking supplies line the back counter, and people are bustling about around the center table. I worked a lot on capturing the organized clutter that fills the building, adding weird and unconventional, yet representative, blocks wherever I could.

Building the site

Once I was happy with that, I got to work on the ditch-filled dirt road that leads out of camp and turned the Minecraft savannah into the fields where cattle, buffalo, and horses roam around. In some areas, these fields seem to stretch on forever, so I ensured I provided ample space for the digital livestock. After all of this was finished, I built the walking path that led to the entrance of the main study forest.

I left the generated forest more or less the same; all I changed was that I added some of the transects that we use to navigate the forest. Although in real life, these transects are a bit less neat and a bit more confusing for my colorblind self, who often struggled to distinguish the marker flags.

Monkeys also live in forest patches separated from the main gallery forest. I added Colman, one of these forest islands that is quite close to the gallery forest. My favorite group of monkeys lives there, so I really tried to do it justice, but a lot of it was solely based on memory. It definitely should be a bit larger, but I doubt the monkeys will mind.

Adding tiny details

I had a ton of fun adding tiny little details. If you explore the world, you may be able to find easter eggs, like a spot where I would go to the bathroom or somebody’s tent that would always get soaking wet whenever it rained.

All in all, it only took me a few days, where I’d build for a couple of hours. But there are still a ton of things I’d love to add, like making the naturally generated forest more like the real-life version and building the highway leading back to Formosa, the closest city that we’d spend weekends in. Maybe eventually I could build the entire city.

All the files are publicly accessible for free on the OMP Instagram along with instructions to load the world. So anybody with a Minecraft account can explore our site from anywhere in the world. I really hope that people will be able to better understand the site itself, and thus better understand the work we’re doing and everything that goes into it. It would be amazing if other groups built their field sites, and we could have this whole world that people could explore and learn about field research.

If you’re a field researcher interested in building your field site in Minecraft and sharing it as an educational resource, please click here to reach out to The Leakey Foundation.

Gus Dupin is a student at Cornell University and a research assistant at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.