Book Shelf

by Kilbee Brittain

by Kilbee Brittain

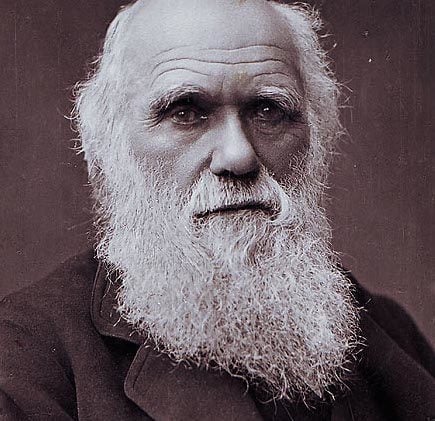

A new book by Ian Tattersall is always a cause for celebration, and The Strange Case of the Rickety Cossack is no exception – with a warning:

It’s a demanding story of old bones, their finders and keepers, their interpreters slugging it out over taxonomy and ultimate meaning. Not a book for an afternoon at the beach, but one to cherish and chat about with good friends who enjoy a challenge. Here are a few highlights:

A Rickety Cossack

The quirky title refers to the strange interpretation of some bones found in the Feldhofer Grotto in Germany’s Neander Tal (Valley) in 1856 by miners looking for lime to fuel the booming chemical industry. An alert supervisor saw bones in the rubble workmen were dumping over a cliff. The cache was shown to a teacher, who correctly identified them as ancient. They were passed along to a respected Bonn anatomist, Hermann Schaffhausen, who concluded they were from a barbarous race of Homo sapiens.

The bones were passed on to pathologist Rudolf Virchow, who diagnosed the fossil as having suffered rickets as a youth, the pain being intensified by his life on horseback, which agony caused him to furrow his brow constantly, his perpetual frown causing his bony ridge across his brow. Fellow Bonn faculty member August Franz Mayer concluded that the fossil had been a Cossack soldier in the Russian army rampaging across Germany in 1814 en route France, and, being wounded, crawled into the Feldhofer cave to die.

Darwin’s good friend Thomas Huxley had a good time mocking this “absurd story,” but did not see the bones as being ancient. But geologist William King announced at a scientific meeting in 1863 that the forehead configuration of the Feldhofer skull represented a distinct human species, Homo neanderthalensis. King’s prescient analysis was almost immediately substantiated by George Busk’s announcement of a Gibraltar cranium with similar features. But public acceptance of this new human species would take more discoveries over the next 20 years.

As more bones were found, 19th-century Britain was in intellectual turmoil over humans’ place in nature, with the biblical idea of man as the ultimate creation. Larger-than-life men stated their views. Alfred Russel Wallace, returned from his strenuous years in Amazonia (including being shipwrecked on the way home and losing all his specimens), left for 7 years in Malaysia, returning with his manuscript proposing “natural selection” as the means of the appearance of new species. He sent the manuscript to his friend Charles Darwin, who had independently formed the same idea on his 5-year trip around the world, and was at work on his magnum opus, The Origin of Species. Darwin was deeply upset at the prospect of being scooped. Huxley set up a debate for Darwin and Wallace at the Linnaean Society.

The resulting ideas, including Darwin’s observation that the African apes and humans certainly shared some similar traits, went “viral”. The oft-quoted horrified exclamation of the wife of the Bishop of Winchester sums up the Victorian view: “Descended from the apes! My Dear, let us hope that it is not true, but if it is, let us pray it will not become generally known.”

1950

The year 1950 is Tattersall’s choice as “the most momentous in the 20th-century intellectual history of paleoanthropology.” The names Mayr, Sherwood Washburn, Clark Howell are familiar to the fans of the subject.

The invention of radiocarbon dating was another gift of 1950, invented by University of Chicago physical chemist William F. Libby, a scientific way of dating fossils to about 40,000 to 50,000 years ago, by measuring the decay of “C” in a sample. The method was used in dating the rock shelter at Les Eyzies in SW France, where sediments revealed a succession of cultures, including “the art-drenched Magdalenian culture.”

“In the post-1950 anthropological milieu strode Louis Leakey,” Tattersall writes. Kenya-born British archaeologist and anthropologist and his wife Mary, also an archaeologist, had been searching East African hills and vales for decades, for signs of early hominids. They had recently concentrated on Olduvai Gorge in northern Tanzania. In 1959 at Olduvai’s lower level of its “layer cake” of time amidst scattered stone tools, Mary found a magnificently preserved cranium (skullcap without mandible, or, lower jaw), with huge molars. Leakey called it Nutcracker Man, a new species, Zinjanthropus boisie. “This weather-beaten, White African couple” had the support of the National Geographic Society, which poured funds into the Leakeys’ work, understanding its importance and sensing a dynamic, continuing story. Soon after, the Leakeys found Zinj’s missing mandible, which they thought made the skull complete and “a new and truly primitive ancestor of Homo”. Louis had a candidate for Earliest Toolmaker!

By using the new potassium argon (K/Ar) dating method on the fossil remains and volcanic ash, a date of about 1.75 million years was determined.

Goodall

Tattersall makes no mention of Jane Goodall in his text or even in the index. Not even in his chapters on the Leakey family. Goodall is celebrating her 55th year of the chimpanzee project at Gombe Steam National Park in Tanzania. Dr. Leakey suggested the study as a project for Goodall when she asked his advice soon after her arrival from Great Britain in 1957. She went to the forest, taking only a native cook and her own mother. Soon she had assembled a small staff and had attracted the attention of the National Geographic, which has featured her work there in numerous articles. Among her many scholarly findings, one stands out as most revolutionary; On November 4, 1960, she watched a male chimp (whom she had named David Greybeard) pick an 18-inch long grass stem, pluck leaves to make the stem smooth, and insert it carefully into one of the winding tunnels of a nearby termite mound, then withdraw it, all covered with termites, and swipe it through his lips to chew up the crunchy insects. He did this numerous times. On subsequent days she saw the same behavior, and cabled Leakey, who cabled back, “Now we must redefine ‘tool’, redefine ‘man’, or accept chimpanzees as human”.

Leakey Vessels

Tattersall urges readers to remember “that closely-related species like Homo Neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens are “very leaky vessels”, but that “no biologically meaningful melding” occurred. Homo Neanderthalensis “retained its morphological identity until it disappeared.”

Our species is extremely young, a short 200,000 years old, with most of our history since we left Africa about 60,000 years ago… We have discarded the idea of human “races” as we have become so mobile (and must guard against its reinstatement). We recognize certain biological markers, and understand that skin color can be a genetic reaction to climate.

In the last 10,000 years, at the end of the last Ice Age, human population has mushroomed and spread, our only barriers now being cultural. But we are not an exception to Nature’s rules “We are the pinnacle of nothing, simply one more twig on what was until very recently a luxuriant evolutionary tree…” (p. 222).

Tattersall tells of his first time in Madagascar and the Comores, studying the beautiful and varied lemurs. He writes of their diversity, their beauty, their adaptability: Noting the diversity in their more than 50 species, he notes that it is not unusual among successful groups of mammals. They have been surviving, diversifying all these millennia, evolving as their very special kind of primate, adapting to climate changes and the environmental destructiveness of their only competitors, who arrived on their island just about one thousand years ago.

Tattersall closes his elegantly detailed study by encouraging humans to take note of our imperfect selves as being no exception to Nature’s rules, like our primate kin, the lemurs. “Odd we may be,” the author admits, “but we are nonetheless an odd primate.”

Bravo Ian Tattersall, for putting us in our place with erudition, flair, and in such good company!

Kilbee Brittain received her BA from Stanford University and her PhD from University of California Los Angeles. For decades, she has been actively engaged with the docent program at the Los Angles Zoo and has been am enthusiastic supporter of The Leakey Foundation for 31 years.

Click here to read the full article by Kilbee Brittain.