George M. Leader of the University of Pennsylvania describes the importance of long term archaeological research at South Africa’s Cantee Kopje, one of many world heritage sites threatened by diamond mining.

Archaeologists working in South Africa are fighting a war on multiple fronts. While the whole world continues its love affair with its favorite stone, the diamond, archaeologists are fighting to save stone artifacts, many of which are destroyed in the pursuit of diamonds. As I write, another important protected site, Canteen Kopje in South Africa’s Northern Cape Province, for which I am one of the permit holders to, hangs in precarious balance, a battle between those who wish to save heritage for millennia to come and those who wish to mine it away in just days.

Field archaeology still has a major role to play in piecing together the story of humankind. New sites provide new clues as to where our hominid ancestors were living and what traditions they were capable of passing along. As the world continues its growth and development, many of these sites become threatened. In the case of the Northern Cape, diamonds have ruled for a century, and anything in the way, has fallen.

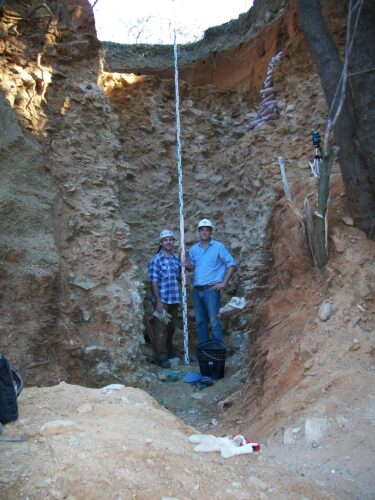

The ancient alluvial gravels, which are packed full of stone tools, also contain small amounts of diamonds. Here archaeologists stand in front of a sequence that dates from 1.7 million years ago near the bottom to 1.2 million years at the top. The red sands capping the gravels contain important later stone age artifacts as well. Photo shows Ryan Gibbon (left) and the author.

You may be familiar with the term “blood diamond” made famous by the film of the same name starring Leonardo DiCaprio. Yet even diamonds that shed no blood when mined can still cause extensive and irreparable damage. Many of the world’s diamonds are found in the same ancient alluvial deposits as the oldest stone age artifacts, made millions of years ago by human ancestors. These stone tools may seem unimpressive to many, but archaeologists will tell you that they are a glimpse into one of the most important periods in our evolution.

The gravel layers are immensely important because of the stone tools embedded within. Studying these early stone tool assemblages allows us to see how our ancestors were living and how their technology was evolving through time. Looking at the technological change through time allows us to see exactly how our ancestor’s cognitive abilities advanced. We can look at how we adapted technologically during environmental changes. The problem is that we need to study them in context. We need to excavate in careful chronological spit levels to make sure the technology corresponds with the dating and the sediment samples. The long time spans saved in these gravel sequences are the prime locations to study our past.

One Site, Many Researchers

Current research at Canteen Kopje has been approached from multiple teams on many fronts. A University of the Witwatersand and University of Pennsylvania team lead by myself and Prof. Kathleen Kuman has excavated a stone tool sequence dated from 1.7 million years to 1.2 million years. The team’s dating specialists, Dr. Ryan Gibbon of the University of Cape Town and Dr. Darryl Granger of Purdue, used cosmogenic nuclide burial dating to calculate the exact ages of these tools (publications in final preparation). The 15,000 stone tools display simple manufacturing techniques in the early dates with continual advancement of technique through time, an incredible show of hominid cognitive ability and skill only found in a long sequence like Canteen Kopje’s. Dr. Vincent Mourre of INRAP in France is working on replicating the Victoria West prepared core. This stone artifact demonstrates incredible knapping abilities of the hominids, and we don’t fully understand how it is made.

The technology above the youngest alluvial gravel layer has even younger “Fauresmith” technology which is unique to the region and is a final period of the Acheulean technological tradition as hominids transition into modern human. These tools are being extensively analyzed by Dr. Kathleen Kuman and Kelita Shadrich for her master’s project. She will be using spatial analysis methods assisted by her supervisor Dr. Dominic Stratford of University of the Witwatersrand. They are only able to fully understand the contact point between the gravels and the Fauresmith levels because of the geoarchaeological work conducted by Matt Lotter, a Ph.D. candidate at University of the Witwatersand. Dr. Tim Forssman also of University of the Witwatersand has analyzed the Later Stone Age component of the site which lies in the red sands that prominently give the site it’s color.

On the other side of the Canteen Kopje another team works diligently to understand these same later stone age periods and the colonial contact periods as new peoples moved into the region. The team lead by Dr. Michael Chazan of University of Toronto, Dr. Alex Sumner of University of New Brunswick and Dr. David Morris of the McGregor Museum in nearby Kimberley lead the most recent fieldschool for students from the new Sol Plaatje University in Kimberley with great success. Students who would normally never be exposed to archaeology have a chance to not only learn excavation techniques but to experience a site of international importance in their own region.

Canteen Kopje has a record of human ancestor activity from ca. 2 million years ago until modern day. The site is worked on by archaeologists from three continents. It has hosted more than 60 university students on fieldschools. Yet, the even as a designated heritage site, the threat from diamond mining is real.

Early handaxes like these are a pinnacle of our ancestors’ technology 1.5 million years ago. Mining the site will destroy thousands of these.

Diamond miners working in South Africa today can still be profitable finding just 1 carat per 100 tons of gravel that is scooped out. To be clear, 100 TONS of gravel for 1 carat of diamonds. In other words, for just one pea-sized stone, a company might dig up 10 medium sized cars worth of gravels. This doesn’t even necessarily include the sands that cap the alluvial gravel layers.

While H. ergaster might have been unaware of the precious stones he was sitting on while knapping stone tools such as handaxes, we are aware of the stone tools being destroyed in the mining process. All mining companies are required to get permitted approval with South African Heritage Resource Agency (SAHRA) for each and every site. Additionally, the Department of Minerals and Energy (DMR) also needs to issue a permit. The two permits together then equate a green light for the project.

Unenforced

The author takes samples from a 1.3 million year old layer containing stone artifacts during active mining operations near Windsorton, South Africa. The thin dark layer near the bottom is the only layer containing both diamonds and stone tool artifacts.

South Africa’s heritage and world heritage has been hit yet again with a devastating blow by miners. In March of 2016 mining began on Canteen Kopje. In addition to containing more artifacts in it than any other gravel site in the entire region, the site boasts a monument and information pavilion as well as a marked path for tourists to walk and guide curious motorists around the site. All these are efforts to encourage tourism and appreciation for heritage.

In 2014 the Department of Minerals and Energy (DMR) issued a permit for mining to take place on part of the declared site. SAHRA was alerted, and in response, because of the existing formal declaration of the site, a “Cease Works Order” was issued. Pressure (and whatever else helps things move along under the table) came from the miners, and in March 2016 the Cease Works Order was lifted. Still no known SAHRA permit has been issued. The mining of a declared heritage site is a crime in South Africa, specifically noted in section 27(18) of the National Heritage Resources Act (NHRA) (Act 25 of 1999), which states that: “No person may destroy, damage, deface, excavate, alter, remove from its original position, subdivide or change the planning status of any heritage site without a permit issued by the heritage resources authority responsible for the protection of such site.”

The law continues: (Section 51. (1) of the NHRA states that) “Notwithstanding the provisions of any other law, any person who contravenes— (a) sections 27(18), 29(10), 32(13) or 32(19) is guilty of an offense and liable to a fine or imprisonment or both such fine and imprisonment as set out in item 1 of the Schedule.” The age old question remains; is a law a law if it’s not enforced?

Sadly, for Canteen Kopje, a site I have worked on for ten years and others have nurtured for many decades, it may be too late. With the right equipment ten or fifteen acres of the site can be ripped out in just a long weekend, and as if it was planned carefully, a long holiday weekend was just the time the mining began.

In the short term, a handful of miners will make a (relatively) small amount of money from the diamonds, but forever the heritage will be lost. The tourism that will come, the scientists that will continue to come for years and years, and the students who would learn to excavate all will no longer have a reason to be there. The once celebrated site of Canteen Kopje will cease to exist.

Students from Sol Plaatje University on field school learn excavation techniques. (Photo courtesy Alex Sumner)

Saving heritage of threatened sites has been highlighted over the years during unrest in the Middle East and elsewhere, but often in times of peace destruction of heritage is overlooked. Every single day sites are lost in South Africa (amongst other locations) to mining. To have archaeologists willing to move in quickly and save as much information as possible is of paramount importance to saving the record of humanity and evolution in Africa. Millions and millions of tons of gravels are destroyed yearly in the pursuit of diamonds. For 30 years we have been able to protect a drop of water in the sea, Canteen Kopje, a tiny parcel of land to preserve the archaeological record among a sea of already mined land.

New legislation must be created by governing bodies to protect world and local heritage, and of equal importance these must be enforced and produce consequences for noncompliance. Archaeologists who are able and willing to act quickly must continue to be empowered to do so to save threatened sites, and funding bodies must continue to take seriously short notice funding requests for critically endangered sites.

One of the mining pits at Canteen Kopje that was dug in less than 24 hours in March 2016 before a halt was ordered. Over 2 million years of the archaeological record are destroyed. (Photo anonymous)

South Africa and other African nations will (and should) continue to focus on development of economies and the health and wellness of their citizens. But these worthy pursuits do not need to come at the expense of the heritage that reminds us how we arrived here. The record of our ancestor’s lives is valuable for many reasons from understanding cognitive evolution and early cultural adaptations to recording the adaptive technological adjustments during environmental changes.

During the March 2016 mining at Canteen Kopje, due to the tireless efforts of Dr. David Morris, assisted by phone calls, emails, letters, social media and petitions, a halt was able to be put on the miners. A hearing has been arranged for April 2016, but this is certainly no guarantee that the site will be saved.

We will certainly lose more sites to mining and development. But with continued efforts on the ground, from professional societies, government organizations and funding bodies, we can and must work to cut down the pace of destruction to sites not just in South Africa’s threatened diamond regions, but around the world.

About the Author

George M. Leader has a Ph.D. in archaeology from University of the Witwatersrand. He is currently a post-doctoral researcher in the Laboratory for the Study of Ancient Technology at University of Pennsylvania and an Adjunct Professor at The College of New Jersey.

Comments 2

Hi there, I’m a student journalist for the Wits Vuvuzela and I’d like permission to use one of your photos for an article I’m writing about the Canteen Kopje site.

Can you send us a message through the contact form on our site so we can connect you with Dr. Leader for his permission to use the photo?